Marina Pinsky

3 October - 19 November 2019

Marina Pinsky at the Downer

3 October – 19 November 2019

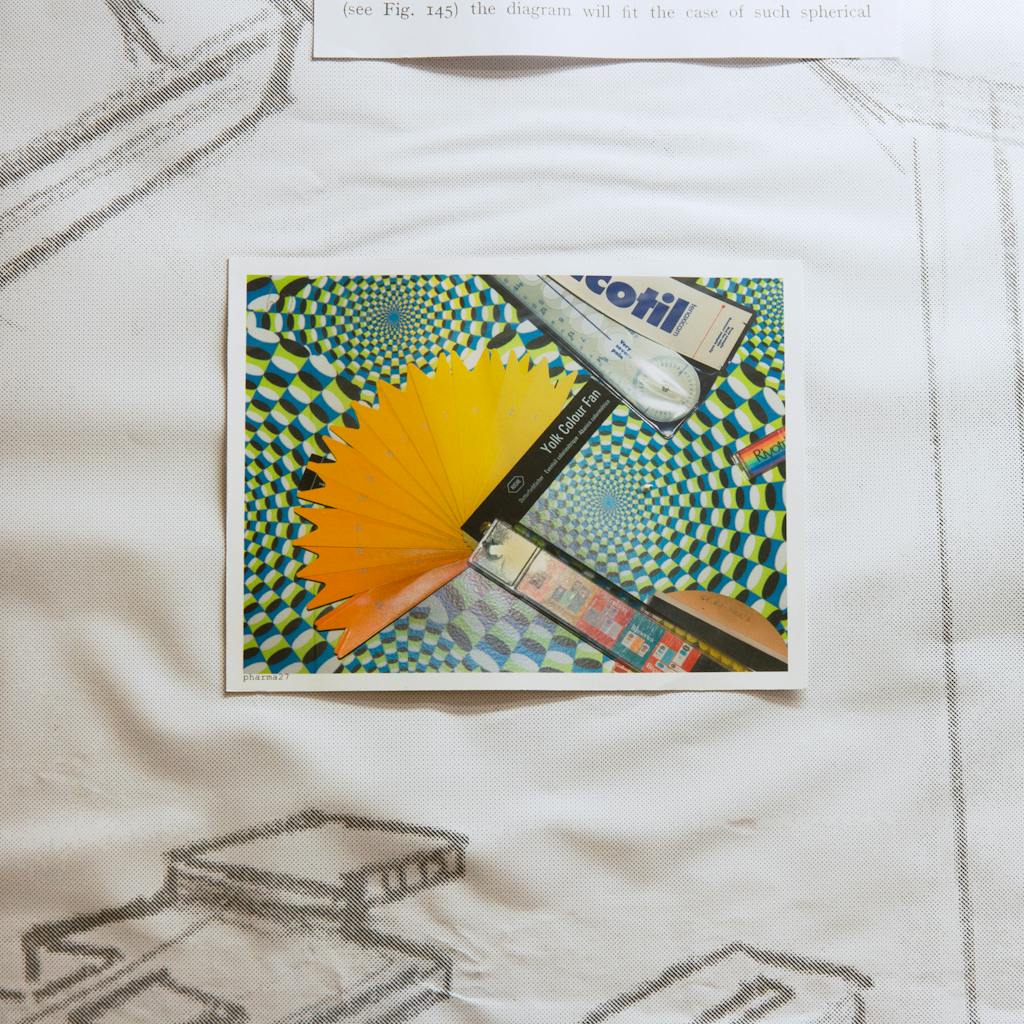

The first piece that Marina and I talked about when we began discussing her show was a fan deck in shades of egg-yolk yellow. The sculpture – which, when fanned out, resembles a gradient sunburst flanked by cobalt blue – is based on an original developed in the early 20th century by the Roche Pharmaceutical Company in Basel. The ‘Roche Yolk Colour Fan’ defined a metric in the farming industry that is still used to this day. Preceding the widespread use of this numbered color spectrum, a scientist at Roche determined the dietary factors that affect yolk color, making it possible to purposefully manipulate the color of chickens’ egg yolks to better suit consumer preference. The numbered system followed and egg producers reacted accordingly. In Germany, over 80% of the buying public prefers their eggs to score above a 12 on the Roche scale (a hearty, pigmented orange). So – not owning one of these Colour Fans myself – I can only assume that the eggs I buy must be somewhere around this number.

This sculpture didn’t take the starring role in the exhibition that we initially anticipated, but I think it serves as a point of entry into Marina’s practice, which is regularly underpinned by moments of serendipity followed by intensive research – and vice versa. The results reveal intrigue or absurdity in the margins of otherwise mammoth facets of life – industries like farming and big pharma, as well as religion, policing, and consumerism. These strands of research are nearly always initiated by a specific discovery in a specific place. And while the resulting objects do foreground their locality, Pinsky’s touch allow her works to swell in meaning to confront the big topics that they previously found themselves relegated by.

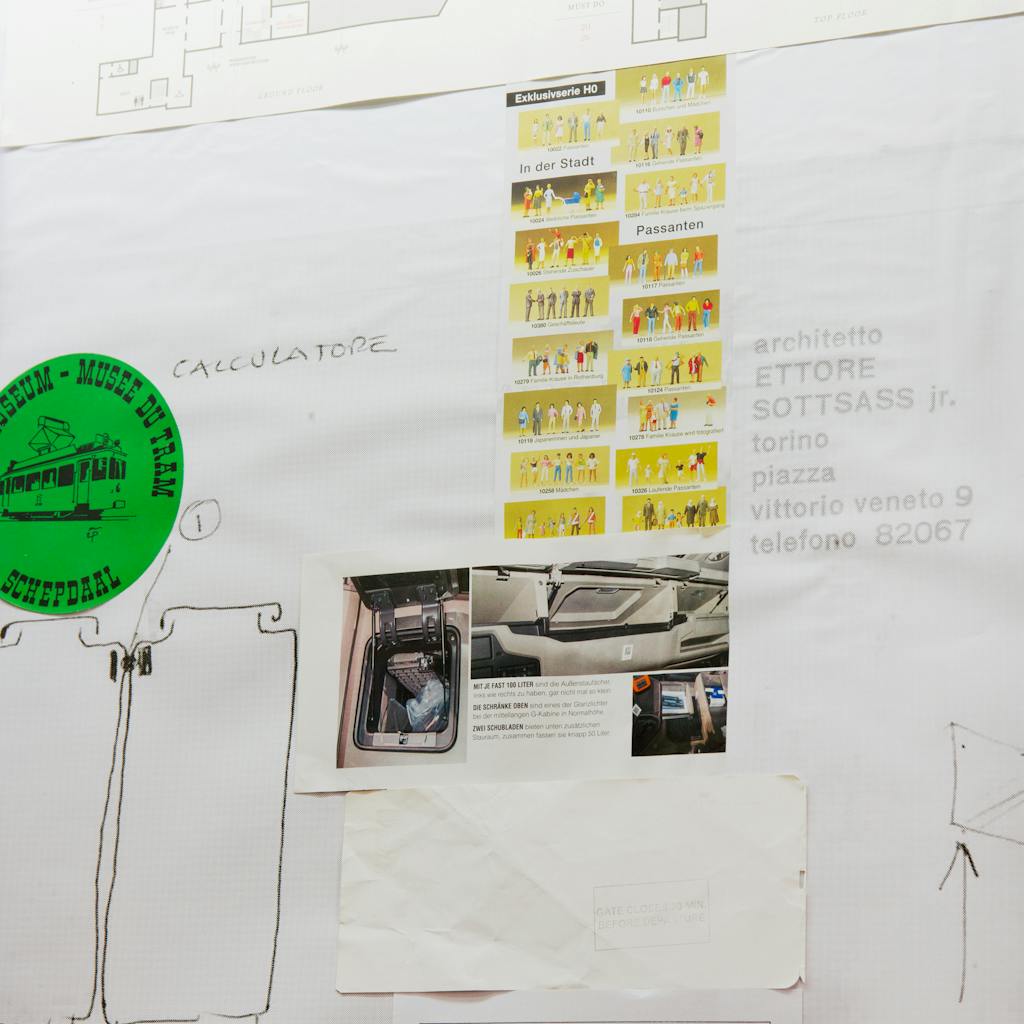

Interestingly, the discoveries that act as waypoints in Pinsky’s larger practice are often encountered on visits to museums, libraries and archives. That the artworks born from these encounters eventually end up back in arenas for contemplation and learning lends to their surreal character. Certain museological approaches are plucked from one type of institution, manipulated and inserted into institutions of a different type. The way in which we frame and present the achievements and failures of humanity – big or small – is an interest of Pinsky’s, and her work furthers this sociological impulse. One could say she builds on top of existent forms – things like novelty collections and museums that are funded by the industries or individuals they canonize – each of them with their own conventions and tactics.

The concept of visiting these pantheons of human achievement is even parodied in her work. A pair of photos that were exhibited some years ago in “Made in LA” at the Hammer Museum depict the view from a box office window in first person, as if we are assisting the patrons on the opposite side of the glass. Two further photos from the same installation feature different views of a modernist glass vestibule. The first shows a line of people waiting in front of a polite looking doorman in a suit. The second pictures people inside the room. It looks like a museum, but there is nothing installed in it.

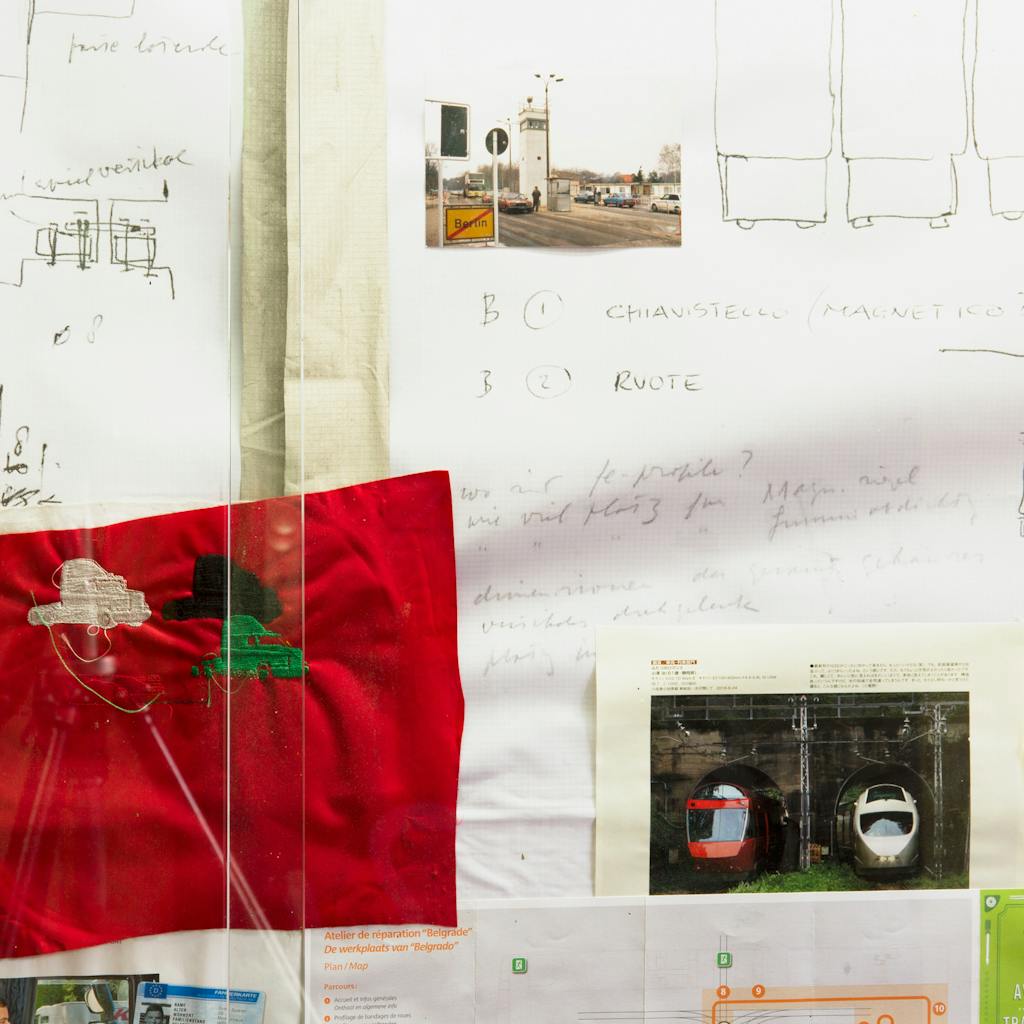

I imagine that the Roche Yolk Colour Fan made its way into Marina’s orbit during the research for her show at Kunsthalle Basel in 2016. Titled Dyed Channel, the exhibition took on centuries of that city’s history, more or less from the perspective of the Rhine River, which runs through Basel and was a fundamental element in the city’s development as a titan of science and industry. Pinsky spent time in a diverse array of Basel’s museums, particularly those devoted to the history of the pharmaceutical industry. Her sites of research included the Pharmacy Museum Basel, the Anatomical Museum, and the Roche Historical Collection and Archive – where I surmise the eponymous Yolk Fan cropped up. Pinsky’s version was carefully crafted by hand and coyly painted in egg tempera, and while it didn’t make it into the Kunsthalle Basel show either, the works that did adopted similar techniques of complicating perception through tactically slowing it down.

The exhibition’s opening room was filled with oversized, “blister” style pill packages containing clay pills, each emblazoned with an image of the progressive architecture that dominates Basel’s pharma campuses. Mostly invisible to visitors of the show were the backsides of the packages, which were decorated with blown up photographs of an abandoned pharmacological production plant in Brussels that Pinsky stumbled upon during the lead up to the show.

In writing about Marina’s work, her particular meld of sculpture and photography is often a subject. She studied with Charles Ray – a sculptor whose work is photographic in its luster and granular detail. Pinsky’s relationship to photography is both more immediate – in that she often does use a camera to take pictures, and more abstracted – in that she tracks the way things and concepts are imaged and replicated, and she inserts herself into this equation. With this outlook a diorama of a train running through the countryside is photographic, so is whatever is framed inside a display case, and so are pills, which are constantly replicated and identifiable through their shape, color, logo, packaging and so on. Photos in this metaphorical context are defined by what they replicate and what frames them.

This attitude is present even when the resultant artwork is more or less a photograph in the common sense of the word. A photograph from 2013 called Gaussian Blur – presumably for the Photoshop filter employed in its making – pictures a half dozen spray-top cleaning products, their labels blurred to the point of illegibility, except that we can still recognize them by their trademark color pallets and a hint of obfuscated graphic design. It’s like a purely visual illustration of the perceptual phenomenon that allows us to read words, however badly scrambled, so long as the first and last letter are correct. Everything else in the photo is sharp; it’s just the labels that have been blurred, like old music videos. The bottles are arranged atop a cloth backdrop that seems to be based on popular East African textiles, which have their own tangled colonial history. It also seems that Pinsky has had this example custom made (or perhaps its discovery spurred the photograph all together) – its pattern is dotted with illustrated spray-bottle motifs. In front of this tableaux, a hand holding a bottle reaches in from stage left and breaks the fourth wall by spraying, it seems, on the inside of the frame’s glass. Gaussian Blur is what you could call a studio photograph – and it is one of Marina’s more self-contained artworks. It is structural, layered, humorously self-aware and rewards attentive looking.

The studio photograph is a category that Pinsky has made uniquely her own. Not only through the careful staging of works like Gaussian Blur, but by turning the studio itself into a supporting actor. She has grown plants for the purpose of featuring them in photographs or has used the studio a kind of loupe, stacking transparencies in front of its lens. Returning to the exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, a series of photographs was included that depicted the view from the window of Marina’s Brussels studio. Partially occluding the rooftops and adjacent buildings are transparencies of microscopic cells and old 4x5 negatives that she discovered in the abandoned pharma plant in Brussels. This temporal and geographical collapse combines trains of thought and tracts of life – microscopic and macroscopic. Literal representations of interiority and exteriority are confused. The cellular scrim almost gives the sensation of looking out of a body. Despite the fact that we have no relationship to it – the photograph begins to represent a view from inside of ourselves.

Our relationship to our surroundings – be they places or things – is something that Marina’s work throws into high relief. History and the present appear as a simultaneous experience, like a polyrhythm or overdubbed vocals. Pieces of long buried histories are unearthed and braided together with much more recent ones. Our engagement with seemingly enduring societal structures is parroted back to us with a question mark at the end. A lot of these questions have to do with humanity’s creation of industry and how much it has shaped our lives. How are things invented, designed, marketed, moved around and consumed today? How do these machinations resemble those of the past? The origins of industry are understandable, just as the basic principles of capitalism are. It’s easier to think of these things in an infantilizing or superficial way, so we often do. To plumb their real depths can be – at least for me – really unpleasant or just logistically difficult. Marina seems to have the opposite disposition. She digs until the shovel hits stone and then stuffs objects full of their previously buried histories.

Patrick Armstrong