Lucie Stahl - "Berlin Babylon"

17 November 2018 – 19 January 2019

Lucie Stahl - “Berlin Babylon” at the Downer

17 November 2018 – 19 January 2019

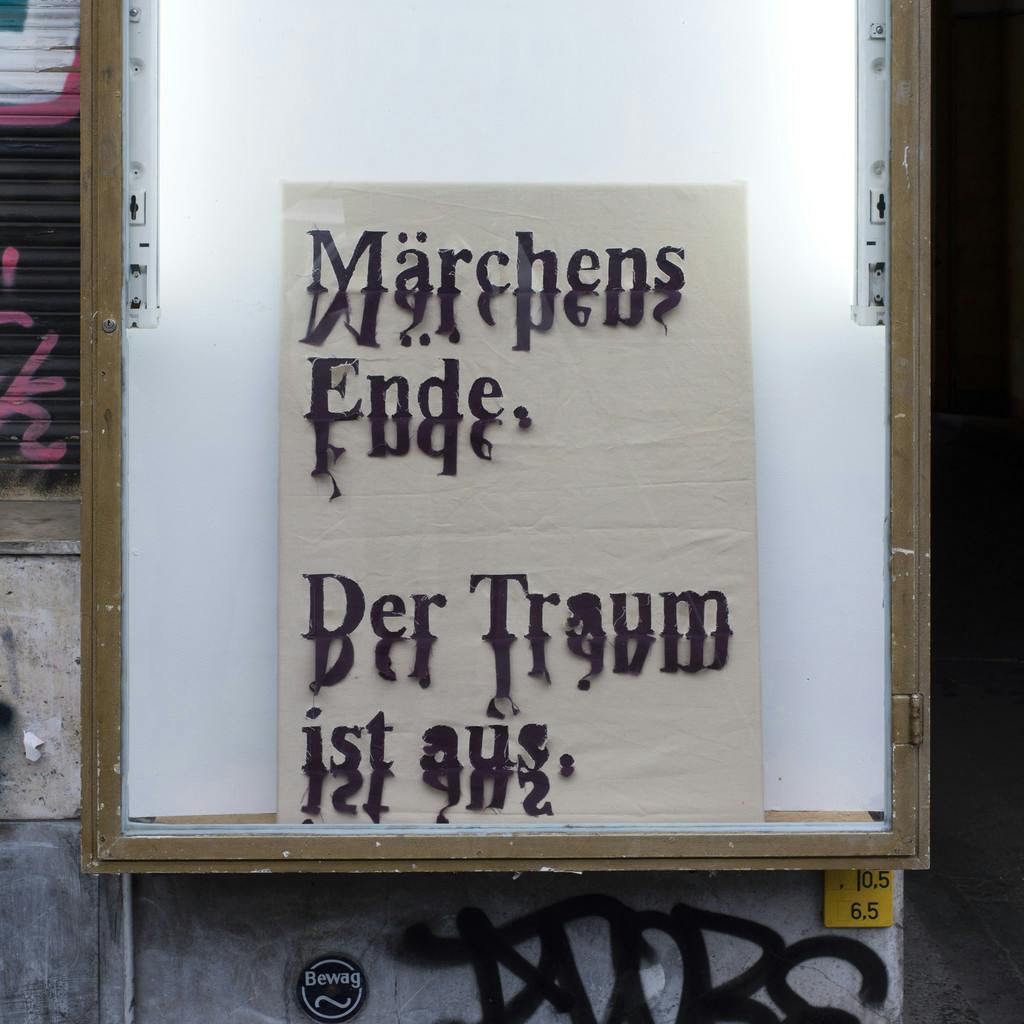

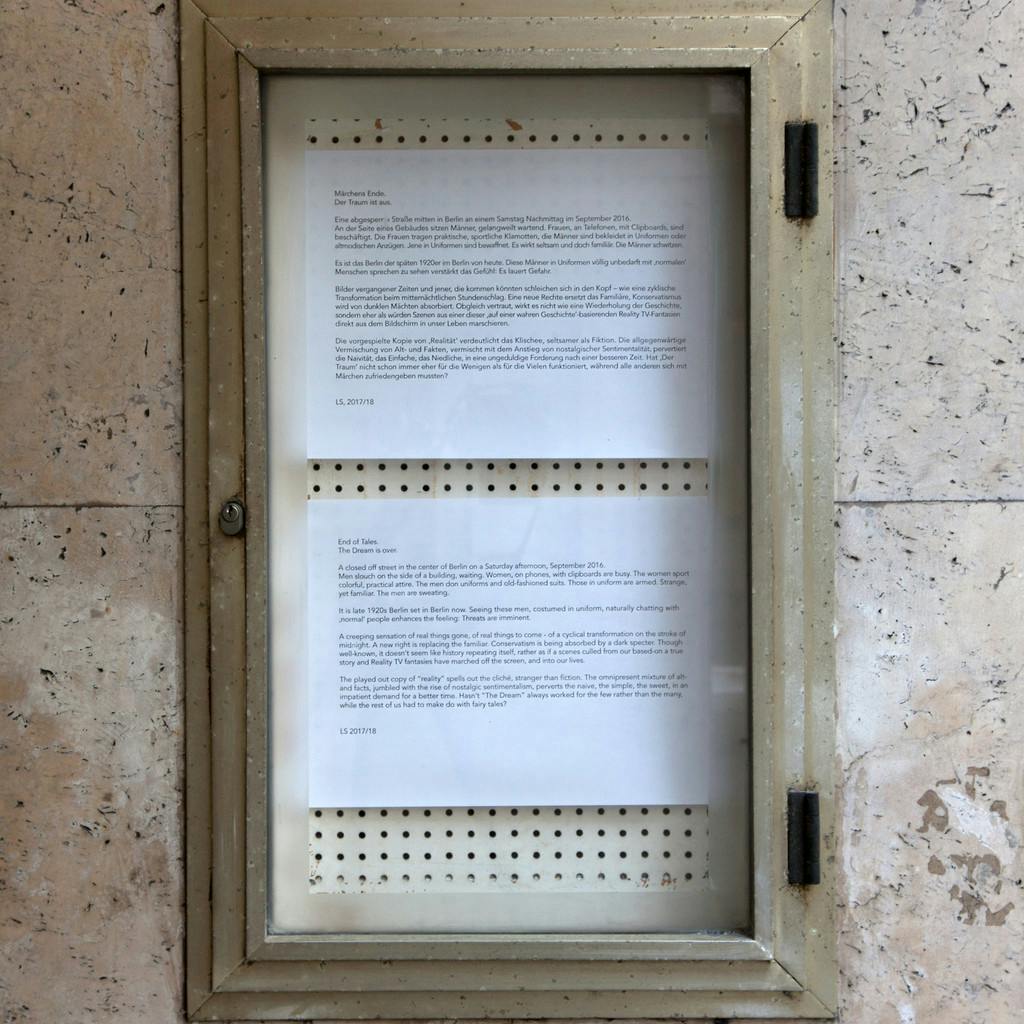

The period television series Babylon Berlin takes place in the riotous Berlin of 1929 – a time when the city was reeling from the shameful fallout of the First World War and was, for perhaps the first time, a world capital of culture. The insidious rise of Nazism was already well underway, with Joseph Goebbels directing gangs of brown-shirted thugs to skirmish with communists and harass Jews. The National Socialist party had won 10 seats in the Reichstag the year prior. At the same time, the city’s three opera houses were packed. Artists and writers moved in, flocking to Berlin’s bars and cabarets. Lavish parties were thrown night after night. Cocaine consumption was at a pinnacle.

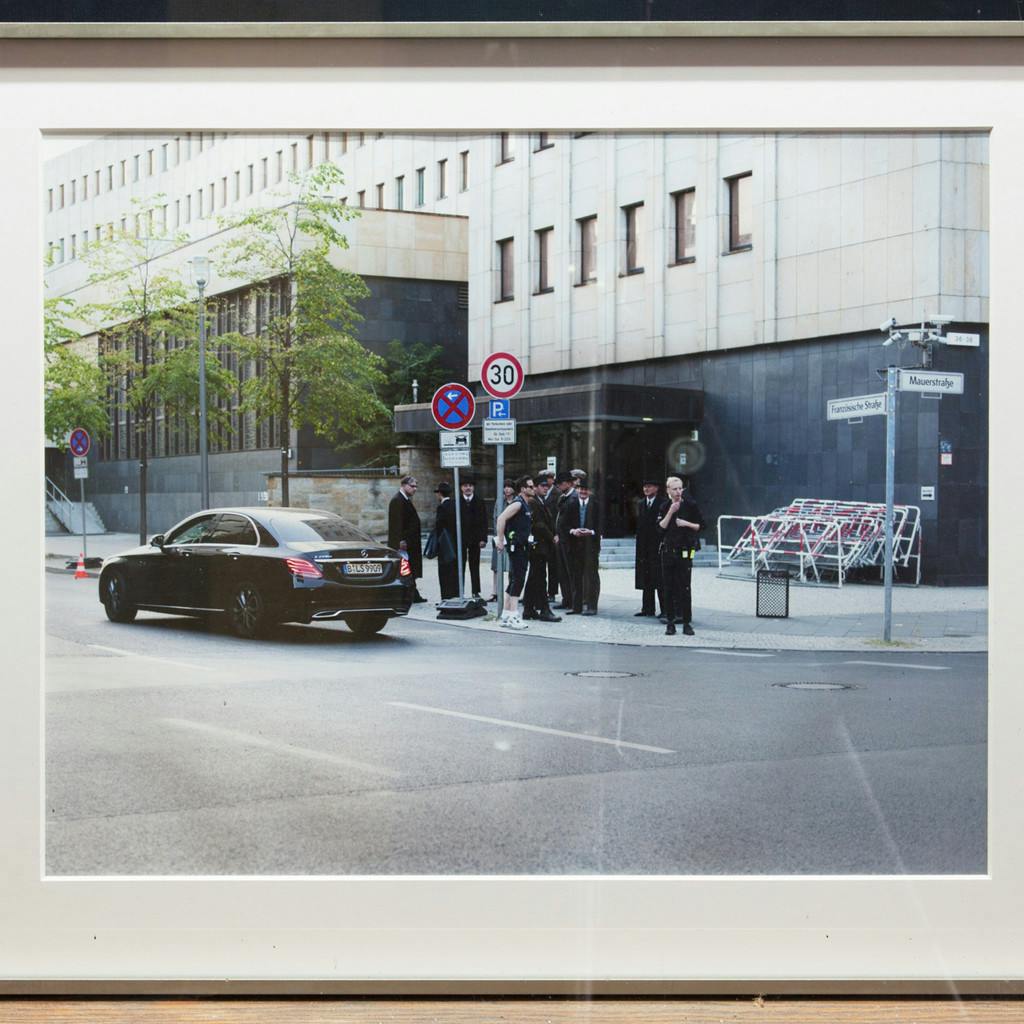

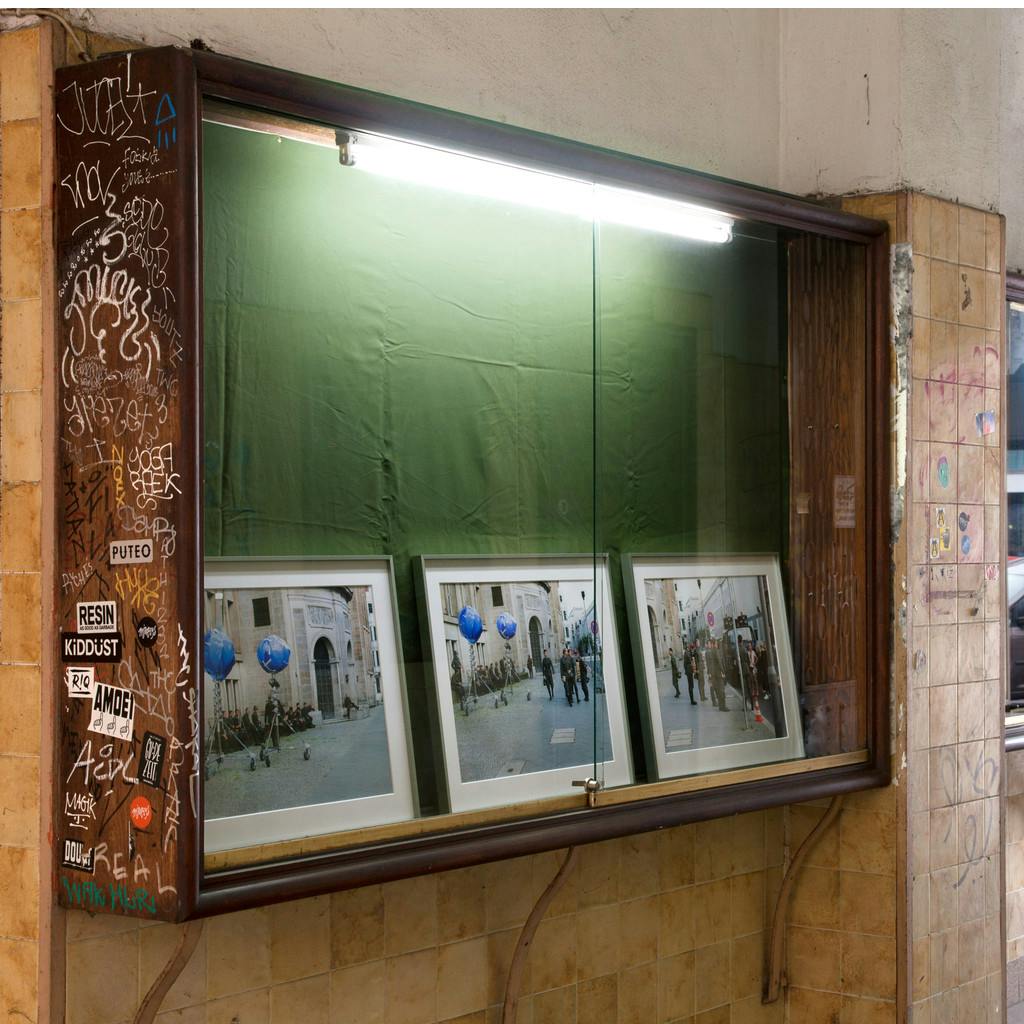

Babylon Berlin has been shot – at least in part – in the eponymous city, occasionally turning contemporary Berlin’s subway stations and street corners into historical reenactments. The stage dressings perfectly befit a city that has spent the past decade rebuilding the Stadtschloss. The original 18th Century palace was demolished in 1950 and replaced by the seat of the East German parliament – a building that was itself demolished in 2008 to make way for the new, old palace. Rather than housing kings or politicians, the new Stadtschloss will be home to an extensive collection of art and cultural artifacts when it opens in 2019. This process of historical resuscitation, modification and reclamation is already familiar in Berlin, the most notable example being the Reichstag, which sports a glass dome in an ostensible nod to openness and transparency of government. Notably, before its renovation, the entire building was swaddled in white fabric by the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude: a kind of born-again christening.

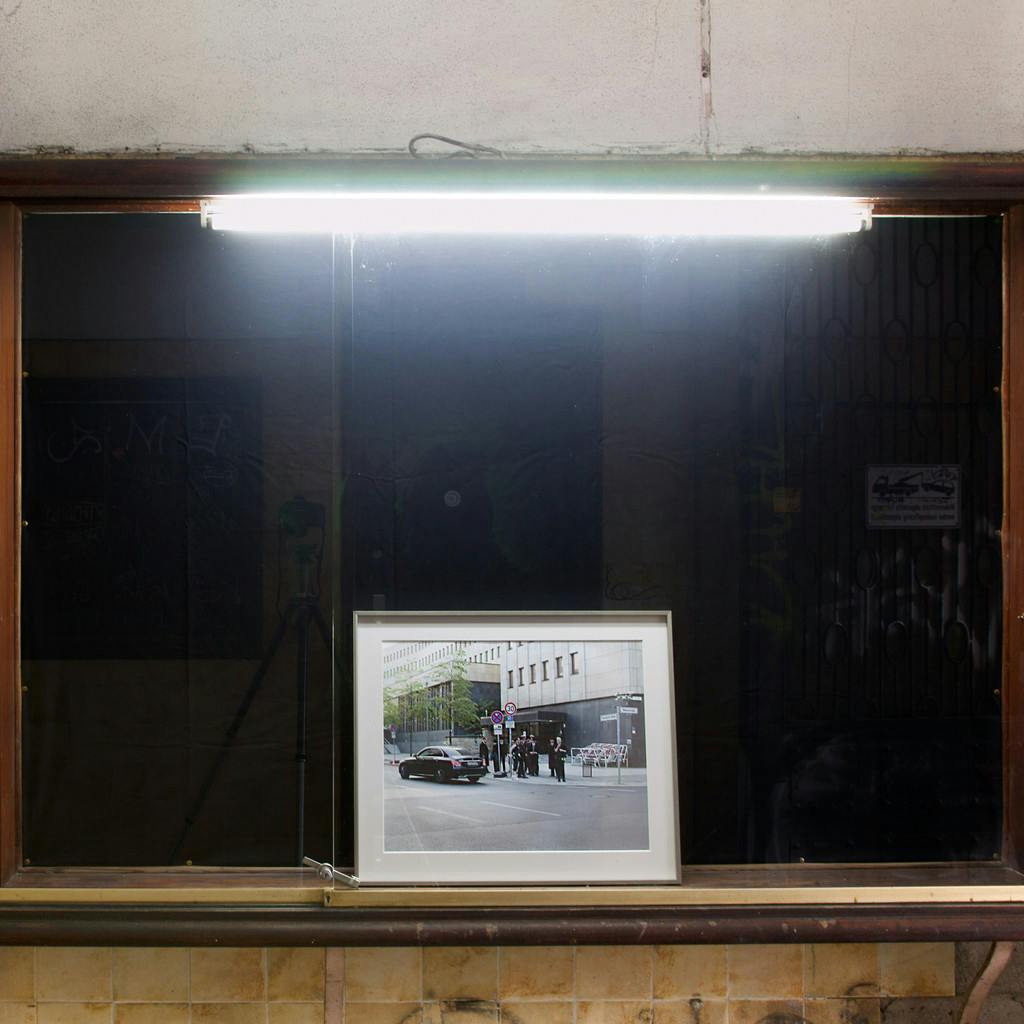

Babylon Berlin’s extras occasionally mill around on the city’s streets, corralled by PAs and prop stylists. Men in Reichswehr uniforms, who would have been demoralized in 1929, fending off putsch attempts and working at the behest of an embattled government, now lounge around, looking somewhat unfamiliar with their rifles. A handful of soldiers are called over and given instructions by people who must be their commanding officers, although they really do not look the type with their neon trainers and fanny packs.

Berlin is once again a global cultural capital with an outsized reputation in the visual arts and music – famous nightclubs and a world-renowned symphony. The city is still home to three operas. Artists have again flocked here. And, once again, social and political dissatisfaction ferments below the veneer of opulence fueled by creativity. Lucie Stahl’s photographs of the cast and crew of Babylon Berlin loafing around between takes on the empty streets of Mitte don’t state this outright, but they certainly intimate.

Intimation, implication in lieu of explicitness, is a hallowed trait of art making – allowing artworks to avoid being too ‘duh’ as well as lending a plausible deniability that could help avoid inviting public outcry or censorship. This is a quality that happens to be shared by advertising, branding, public relations and politics – often for the same reasons. Much of Lucie Stahl’s work doubles this strategy, making a kind of cross-genre mise en abyme in which the show-it-don’t-say-it approaches of branding and marketing are framed within an artwork, therefore demanding to be evaluated on exceptional terms. Arguably, when someone is looking at art they are much more willing to be thoughtful and investigative than when looking at a magazine ad.

In her most widely known series, Stahl uses a commercial scanner to build compositions of consumer objects, miniatures of quotidian things, clippings and advertising. Cobbled together and often held by a pair of clay or paint caked hands – as if dredged up from the swamp of pop culture runoff – each object or grouping thereof feels like a talismanic artifact from our short-term memories. Pressed right against the glass, the murky darkness around them threatens to swallow these objects back up if they weren’t somehow being lit from our vantage point as viewers. There are sleeves of Pringles, bags of Cheetos in increasing grades of sun faded-ness and different versions of the bucolic, salt-of-the-earth genre packaging of health food. There are packs of cigarettes and rocks painted to look like packs of cigarettes; beer cans, to-go cups and bottled water. There are also clippings from magazines: ads, bits of op-eds, even glimpses of artworks, as well as the familiar graphic design of the New Yorker, Economist and Spiegel magazines. These scanned presentations are flecked with bits of dust, dirt and pollen, or occasionally smeared with something viscous that looks like it is slowly drying, out of reach behind a layer of glossy polyurethane resin. Every one of Stahl’s photographs that I have seen in person is lacquered with the same glassy resin coating. It is impossible not to equate this material sensation with looking at a screen.

This is not to say that seeing one of Stahl’s photographs is comparable to seeing an ad for Cheetos on your iPhone. It’s more like checking your bank statement on your iPhone and being forced to recount what you spend 38 dollars on at two in the morning last weekend, and remembering that you bought Cheetos, a case of Coors, a pack of American Spirits and a bottle of water for the morning. The muddy, proffering hands are empathetic – they’ve clawed back to the surface of the same swamp we’re all treading water atop. While Stahl’s work is clearly critical of contemporary life, she remains an individual navigating it. This feeling of knowing companionship became clear to me in her series that appropriates the packaging design of an alternative grain: quinoa or something. The central motif is a silhouetted farmer, alone with his scythe, among peaceful hills and a glowing sunset. The thought is absurd – I know that if I buy a bag of grain in Berlin that was harvested in South America it could not possibly be the product of a one-man operation. But pitted against Chester Cheeto, it’s convincing enough to at least give me a leg up to some moral high ground, and so, I guess it kind of works. The same could be said for her series featuring American Spirit and Pueblo cigarette branding, which laughs at the absurd whataboutism of any cigarette company claiming moral superiority, but again – it works. When branding works on us, life’s little exercises of persona-defining consumer choosiness are almost automatic, quickly forgotten and relegated back to the swamp or tossed out of a pickup truck window into the desert. Stahl picks them up and brings them back to us with alacrity.

In the lonely farmer pictures, Stahl has collaged a rough-hewn door into the side of the hill where the farmer is working. Doors and the keys to them show up in other pieces as well. They seem like invitations to step into the dim world of used and discarded things. This world that Stahl seems to occupy is more than that, though. It is a social subconscious that extends beyond food packaging and into the mechanics of society: the oil business, bad-faith political dealing, insularity and feelings of captivity, environmental decimation and extinction. It’s not actually very inviting, but regardless of whether we enter or not, Stahl will continue to drag things up from the murk and press them against the glass.

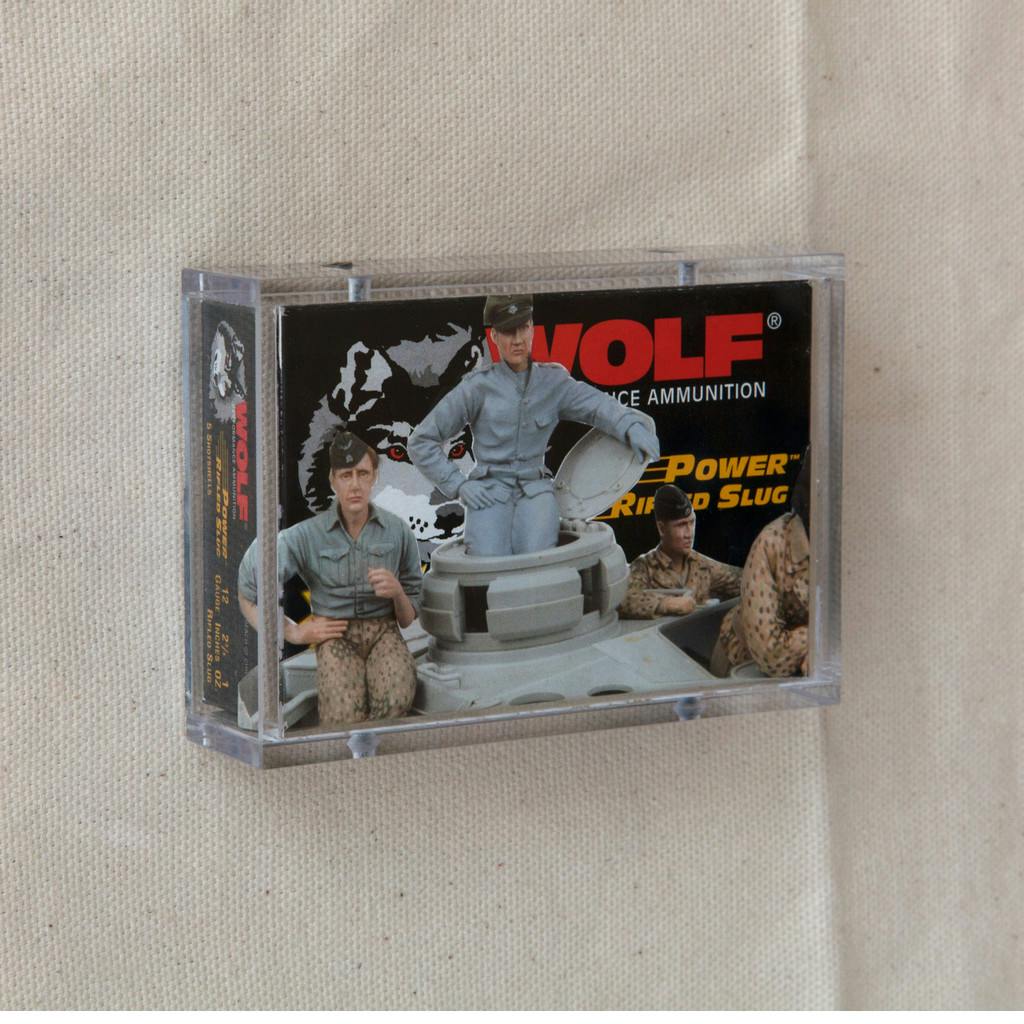

Occasionally, things make it past the glass, like a group of ammunition boxes that the artist collaged over with clippings from hobbyist military model making catalogs. Here a bleak reality starts to be overtaken by the fantasies that drive it, although they too are rehashings of things that happened years ago. Half-painted Waffen-SS soldiers sit atop a Panzer tank, obscuring the part of the ammo’s tagline. The macabre words “Power” and “Slug” bleed through.

In another series, Stahl has made versions of Tibetan prayer wheels out of old beer cans and oil drums. The real Tibetan versions are generally inscribed with a mantra and can be held – and spun – by hand. Their Buddhist originators saw each revolution of the cylinder as one repetition of the mantra. As far as I understand, it’s like praying on hyper drive. Stahl’s versions are like nagging reminders that the world’s production/consumption cycle is on hyper drive and we are subsumed in it, so thirsty for more that we don’t care if it’s a dressed up version of something we’ve already had and cast aside. While she takes up both what we’ve discarded and what we think we desire – be they originals, historical reenactments or bootlegs – Stahl picks apart the conventions that are abused to give these things meaning. Instead, she puts them to work in service of her own worldview.

This feeling of cyclical persistence whether we want it or not permeates lots of Stahl’s practice. The play-acting soldiers in her behind the scenes photographs of Babylon Berlin and the frozen, miniature military men pasted onto a box of bullets both feel like an unwelcome return. There is the implication that we should take care before waxing too nostalgic about sitting at the precipice of a world war and unthinkable genocide. Seeing history uncannily transposed onto the present is a charged experience. The unease is only heightened by the fact that we are living in a time where xenophobia, national exceptionalism and outright racism have found a way out of their cages of socially enforced repression, onto the placards of political parties, and into our daily lives.

Patrick Armstrong