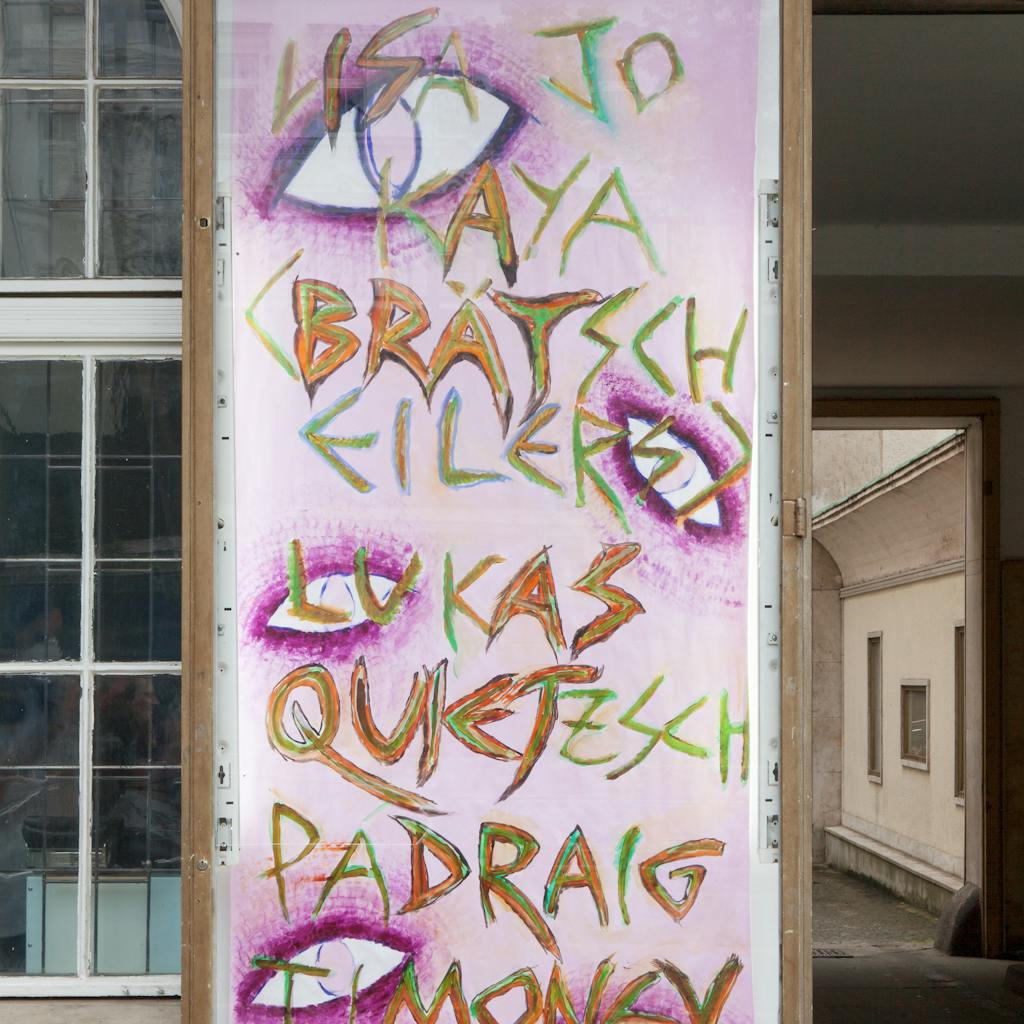

Lisa Jo, KAYA (Kerstin Brätsch & Debo Eilers), Lukas Quietzsch, Pádraig Timoney

16 May - 27 June 2021

Lisa Jo, KAYA (Kerstin Brätsch & Debo Eilers), Lukas Quietzsch, Pádraig Timoney

16 May – 27 June, 2021

I read an article last month about a debate among scientists on how long humans can possibly live. Essentially, one camp believes there is a limit that we’ve already tested — that even with advancements in medicine it will still be extremely rare for someone to live longer than, say, 120 years. The other camp maintains that it should be theoretically possible for people to live twice as long as they do now or more. These opposing contingents were referred to as the pessimists and the optimists.

One of the optimists’ main contentions is based on a long accepted theory that a person’s annual risk of dying increases exponentially with each year they live. But around age 80, this curve begins to level off and eventually plateaus. By the time you turn 105, your yearly odds of dying, while still quite high, don’t get any worse with each birthday.

The many declared deaths and subsequent reanimations of painting have dotted the timeline of art history for nearly two hundred years — probably longer. The whole timeline of late modernity is full of them. The first recorded pronouncement was famously delivered by the Romantic painter Paul Delaroche in the 1830s as he considered the implications of the newly invented Daguerreotype. In spite of this, painting soldiered on, continuing to transform so exhaustively that, in its present state, it would be nearly unrecognizable to its former selves. One could also say that the same transformations are true of humanity — and what is art if not a reflection of its surroundings. For painting, having lived one long, weird life of at least 45 millennia, the pockmarks of 20th century detractors — or any detractors for that matter — have barely even registered. I’m going to take the side of the optimists and imagine that painting’s probability of death leveled off around 5,000 years ago and it has been a perennial winner each year since.

There is a Douglas Crimp essay from 1981 called “The End of Painting.” In it he champions Daniel Buren and takes some pot shots at the exhibition ‘American Painting: The Eighties’ curated by Barbara Rose — which was admittedly a bit of a pompous thing to call a show staged in 1979, but which featured Sam Gilliam, Elizabeth Murray and Susan Rothenberg. Rose, who died late last year, was a big supporter of Minimalism, but was unwilling to allow herself to become a lifelong subscriber to its dogmas. Crimp died two years ago and as the years passed he too began to recant his dogmas, if a bit more belatedly and a bit less eagerly. In the touching conclusion to his book “Before Pictures” He says:

I was convinced that with sufficient insight a critic could — even should — determine what was historically significant at a given moment and explain why. That conviction was a result of my intellectual formation as an art historian and aspiring art critic. Moreover, it was possible to believe such a thing then. The art scene as I experienced it in New York from 1967 to 1977 was small enough to seem fully comprehensible. That, of course, no longer holds true. And because it is so clearly not true now, it seems unlikely that it could really have been true then.

I don’t want to throw Crimp under the bus, but 1981 falls outside of his grace period years. Plus his dogma-tinged take summarizes perhaps the most historicized conspiracy to assassinate painting, while simultaneously providing a nice case study of the medium’s instinctual methods of slithering out of the gallows.

In the text Crimp takes aim at Frank Stella — a onetime demigod of the self-referential program of minimalist painting, and, interestingly, the former husband of Barbara Rose (though Crimp does not mention this). After Stella ‘ended painting’ with his late 1950s series of Black Paintings, he went on to create more colorful and more opulent works. By the time Crimp’s essay was written, Stella was making massive assemblages of cut and curved steel, their shapes like fret holes and french curves, daubed and scrawled on with paint and covered with glitter. Crimp rightly refers to them as “hysterical constructions” and goes on to describe the manner in which Stella’s works after the Black Paintings became increasingly manic repudiations of how his first, most famous series was interpreted. Stella himself, who made the Black Paintings when he was in his early 20s, smugly told journalists at the time, “what you see is what you see.” When what they saw was a useful tool in the fight to push painting over the ledge, Stella realized that he was staring down the barrel of a gun he had inadvertently trained on himself. Naturally, he had to negotiate a way out.

Painting is kind of parasitic — it’s hitched a ride and basically written itself a leading role in the history of humanity. It unquestionably holds the top podium place when the average person is asked, what is an artwork? In Stella’s case, killing the parasite might have taken the host along with. And so, he set out to bombastically transgress every obituary his early works helped write.

Crimp goes on to praise the supposed invisibility of Buren’s artistic project — which, at the time, was painting stripes of uniform width onto unstretched fabric and installing them in unfamiliar or unexpected locations, and in doing so pointing to the conventions and conditions that allow objects to be understood as art. Comparing Buren’s works to painting of the classical definition, Crimp goes as far to suggest that, “when his stripes are seen as painting, painting will be understood as the ‘pure idiocy’ that it is.” The ‘pure idiocy’ part is a quote from Gehard Richter, who in a 1973 interview with Irmeline Lebeer said:

One must really be engaged in order to be a painter. Once obsessed by it, one eventually gets to the point where one thinks that humanity could be changed by painting. But when that passion deserts you, there is nothing else left to do. Then it is better to stop altogether. Because basically painting is pure idiocy.

Crimp conflates artistic passion for critical passion in his text. Just because the passion for painting had deserted him, does not mean that painting’s own lusty zeal had been dampened for one second. Painting always thinks that it can change humanity. One funny thing that comes into focus decades after the high modernist battles about the future of art is that, in the end, the primary vehicle for this discourse could not have cared less. Anyone who has seen Buren’s facade for the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris or his bridge connected to the Guggenheim Bilbao can easily imagine that the same ‘passion’ that took hold of Frank Stella eventually got to him too.

Painting is like whataboutism in the face of high minded reason. On the whole, it is fully unbothered by its detractors and lumbers on, buttressed by history and money. Like Don Draper telling some irate underling that’s trying to shame him, “I don’t think about you at all,” or the meme of Joe Biden eating an ice cream cone, ostensibly running the free world, but so demented he doesn’t know where he is — painting is the Chad in the dichotomy.

Being too big to fail is both a blessing and a curse. The immediate legibility and historical baggage that painting brings with it make it an easy thing to engage but a difficult one to fully get. I didn’t set out to write this text through a bunch of citations from art criticism, but after indulging myself for three pages, I realize that theory, criticism and self-obsession within the world of painting is another part of its enduring allure. To try and fast forward to the present: the many deaths of painting debate eventually gave way to acquiescence that there are far too many heads on the hydra. One vein of painting criticism then began to ask how well the crotchety old medium could reflect our present, which was overwhelmed by commercialization and increasingly informed by the speed and breadth of information afforded to us by technological advancement. Unsurprisingly, certain approaches were lionized while others were relegated. These hierarchies were then questioned and sometimes revised, and the discourse hummed along. A certain amount of combative journalism is part of the medium’s lifeblood.

To be part of this invincible thing that is constantly at war with itself is exhilarating — because, while painting as a medium is basically unassailable, the complicated metrics that categorize artists and movements within this superstructure are eternally shifting, contradicting themselves and reorganizing. Trends come and go with increasing frequency. Institutional support is vied for and occasionally manufactured. Idol worship and speculation run rampant.

If this abbreviated history of painting is starting to sound like a recap of late capitalism, you’re not crazy. In Crimp’s essay, which pits neo-expressionism against the intellectually devised austerity of someone like Buren, there is the tacit argument that frothiness of the art market is another signal of the death of painting. “The End of Painting” was written around the time of Julien Schnabel and David Salle’s sold out first shows at Mary Boone, as well as other star-minting events like the first exhibitions focused on the Neue Wilde in Germany, and a 1980 Venice Biennale that prominently featured big, expressive painting, including the “hysterical” Frank Stella. This is a prescient undertone. The ballooning influence of money in art has become a central theme in lots of art criticism — with painting considered a worst offender for myriad reasons.

To be a painter now requires twinned appreciation and revulsion towards its triumphs. Most painters who have made enduring contributions to the medium in the wake of everything mentioned above began from the conceit that the current state of painting was indulgent, embarrassing, contrived, sexist, useless, or all of the above. But none of them doubted the aliveness of the medium, for better or for worse. One of the most foundational shifts in artistic thinking in the last century is the displacement of self-referentiality by self-reflexivity. To be a good painter takes both. In the microcosm of painting you can question everything about the pursuit but questioning pursuit itself leads nowhere — it can’t be halted. This understanding is one shared by the artists collected here — each reveres the medium’s best qualities while finding novel ways of debating its worst.

Lisa Jo’s contrived abstractions could not have been made without a digital tool that imperfectly replicates the tactile experience of making a painting. In a way they are a stack of skeuomorphism — an imitation of one thing imitating another. This uncanniness is apparent from first glance, but the how and why take longer to work out. The painterly falsehoods that are programmed into the iPad app, but remain untranslatable back into oil, create a tension between the artist’s hand and the synthetic perfection of the digital mark. Once returned to paint, there are revealing fissures in facture, changes in opacity, line weight and texture that are inherent to one medium but not the other. Yet, Lisa’s compositions, while clearly painted, don’t coalesce into something that fits the schema for painterly abstraction. They picture a venn diagram between digital and physical with nothing yet noted in the overlapping center. The search to find shared qualities then falls to the viewer, making her meditative and ultimately foredoomed labor of copying an algorithm productive in its failure. It’s hard not to savor the slippages and rough edges as if they were a reinforcement of our humanity.

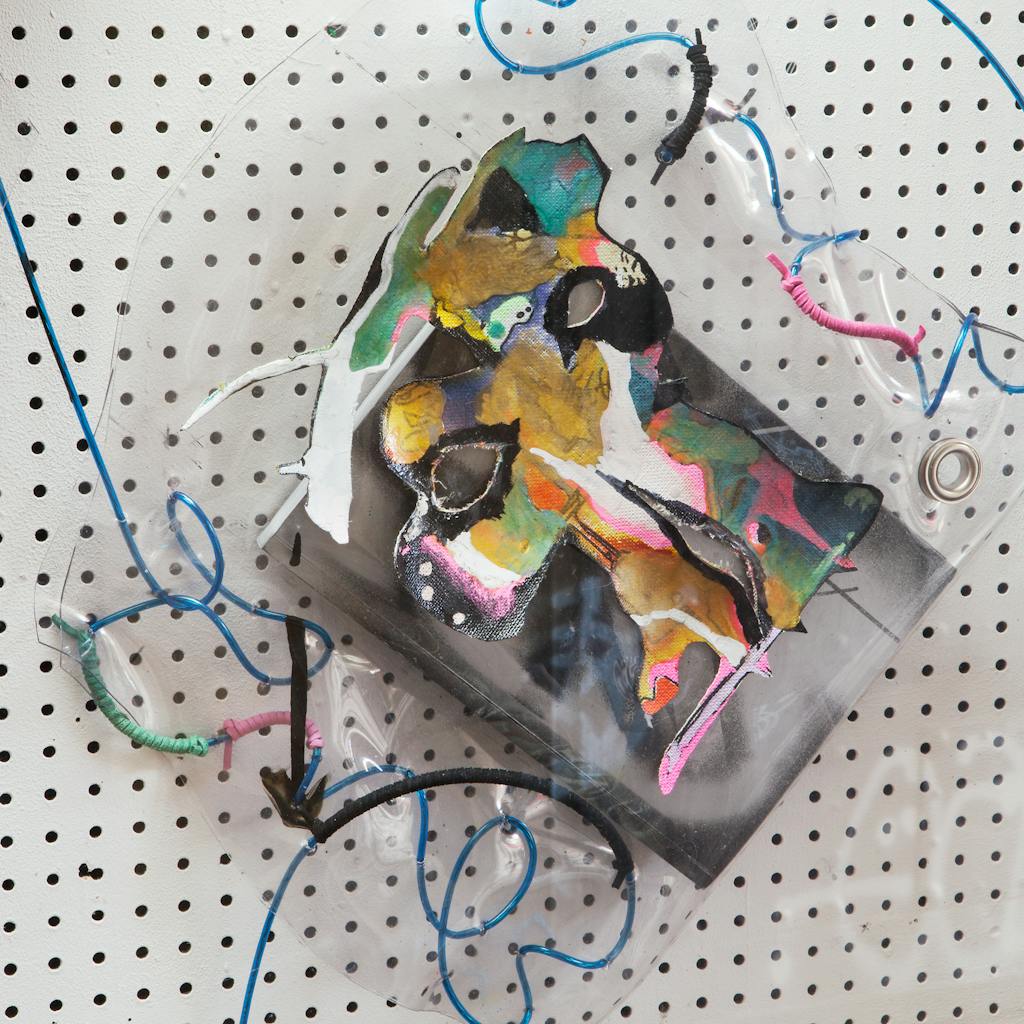

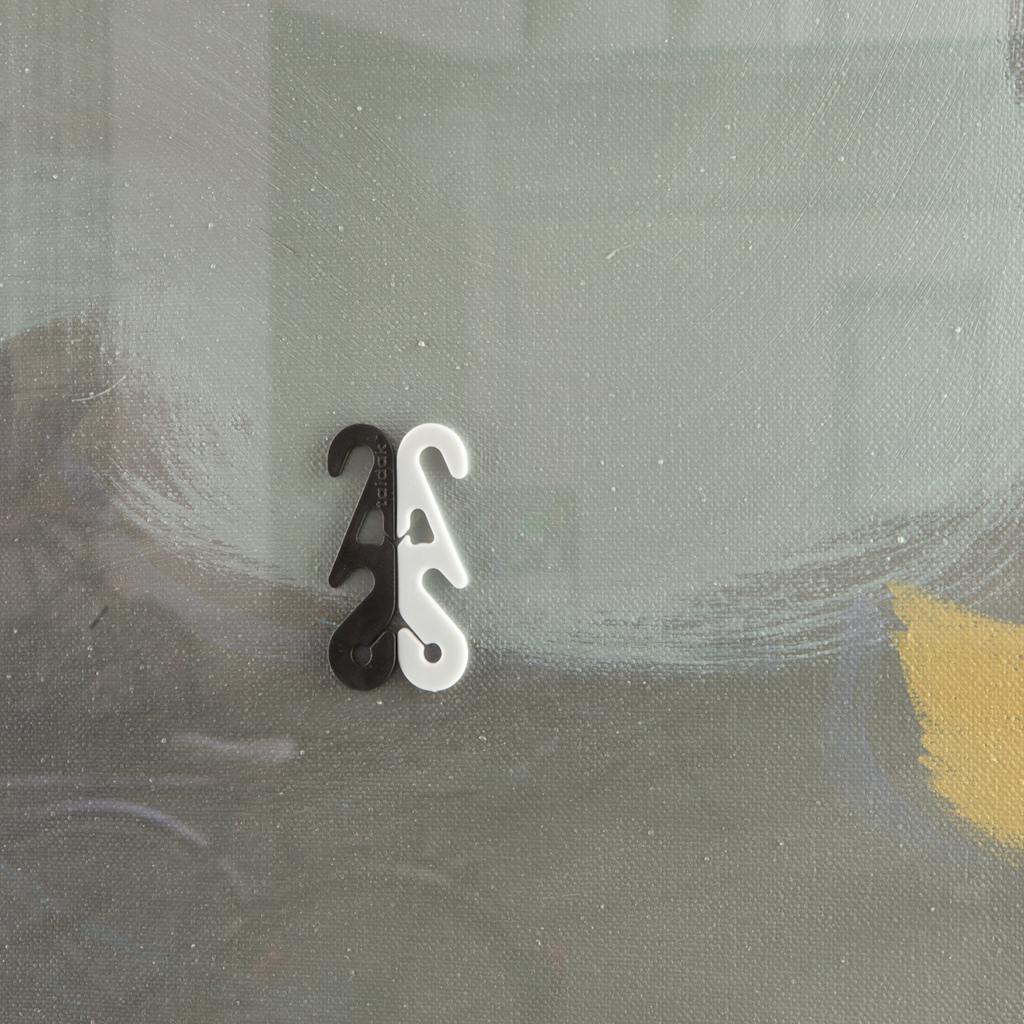

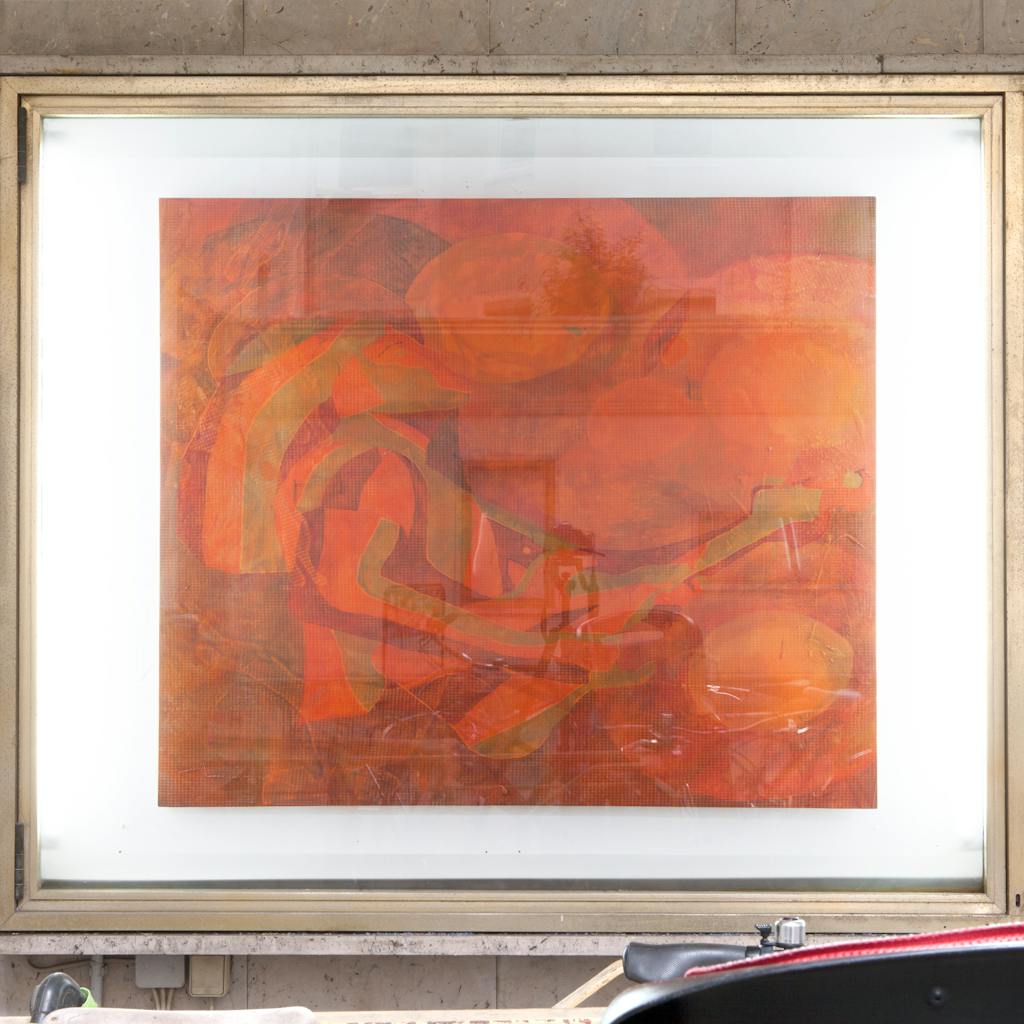

KAYA’s (Kerstin Brätsch & Debo Eilers) talismanic paintings caricaturize authorship, surface, support, brushstroke and reception — essentially every structural aspect of the medium. Often painted on transparent mylar that shows whatever is behind it, the painted surface is not some window into a mimetic fiction, but rather, like a real window, a view onto whatever it’s hanging in front of. They are also usually tied or strapped down, as if they could escape without being restrained. Or maybe the hardware is functional, as the artists and their interlopers have dragged these types of things down the dirt roads of a Western-themed film set Agoura Hills, hauled them up to a mountaintop in Austria and lashed them to the side of a miniature house in more cities than one. It’s almost as if they are trying to assert that an object can also have an experiential memory — or even begin to have an inkling of its place within the timeline of humanity crafting objects with no concrete function. KAYA’s works are collectivized first through the partnership between Brätsch and Eilers, then further displaced by the pretense that this collaboration is named after a third person, a real Kaya, who is implicated as a muse, co-author, or recipient of the works created by the other KAYA. In this instance — and in a number of other recent bodies of work — the graffiti artist N.O.Madski joins the collective. Graffiti adds another confounding metaphor to the mix: it is something unwittingly seen by many but generally sought after by few.

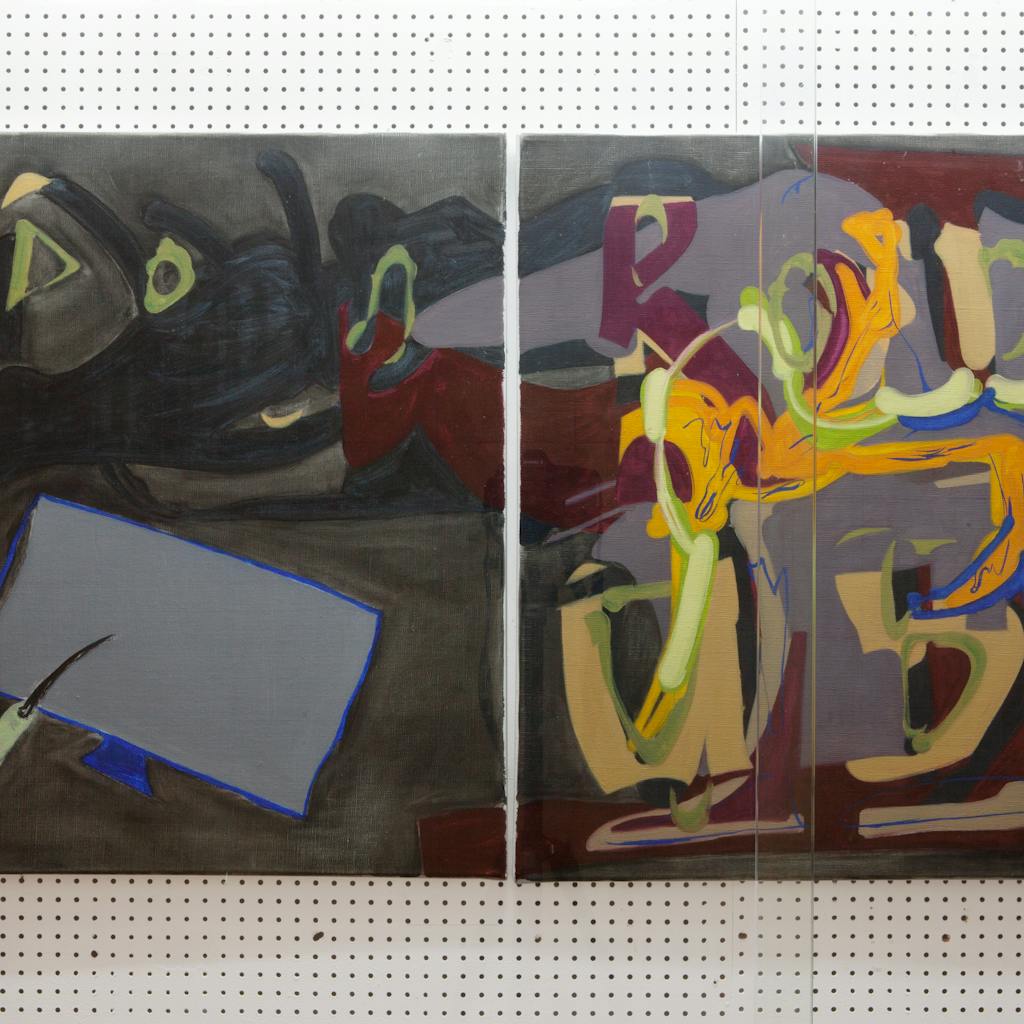

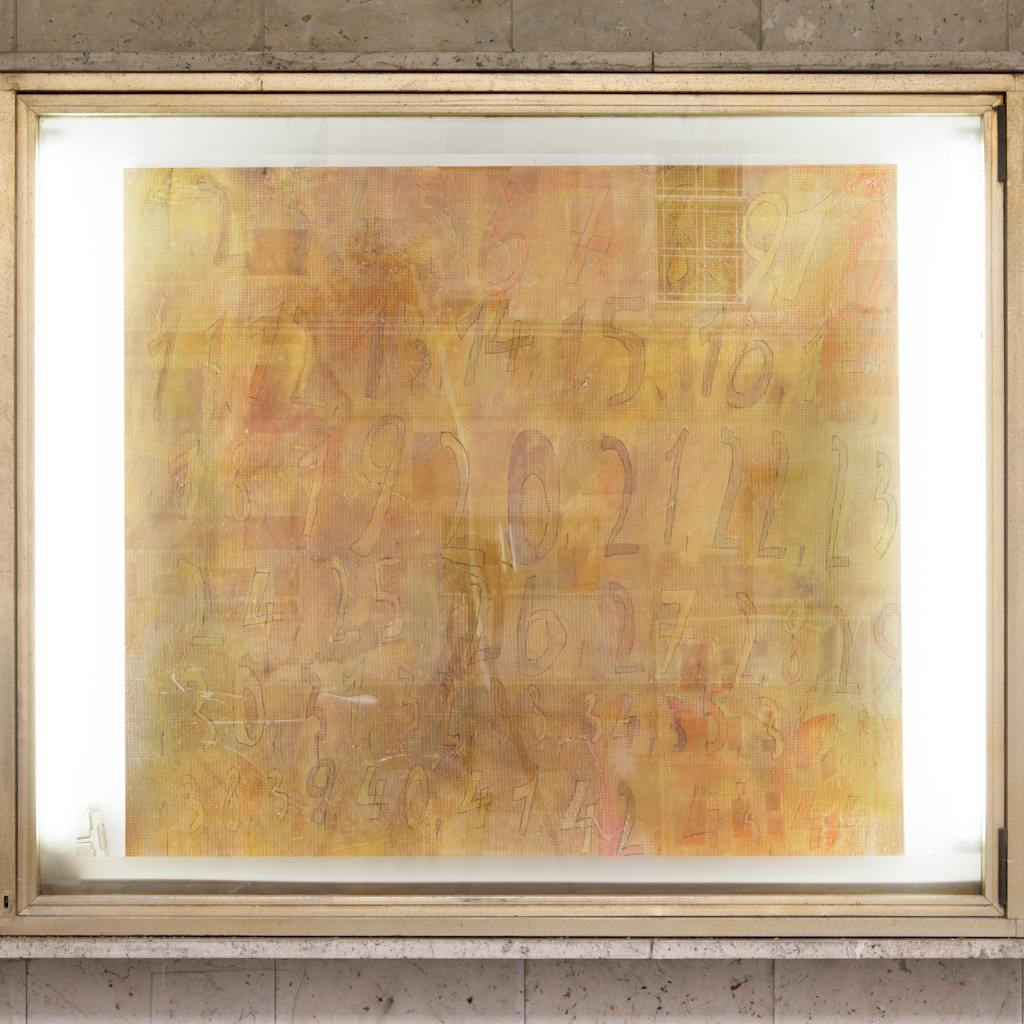

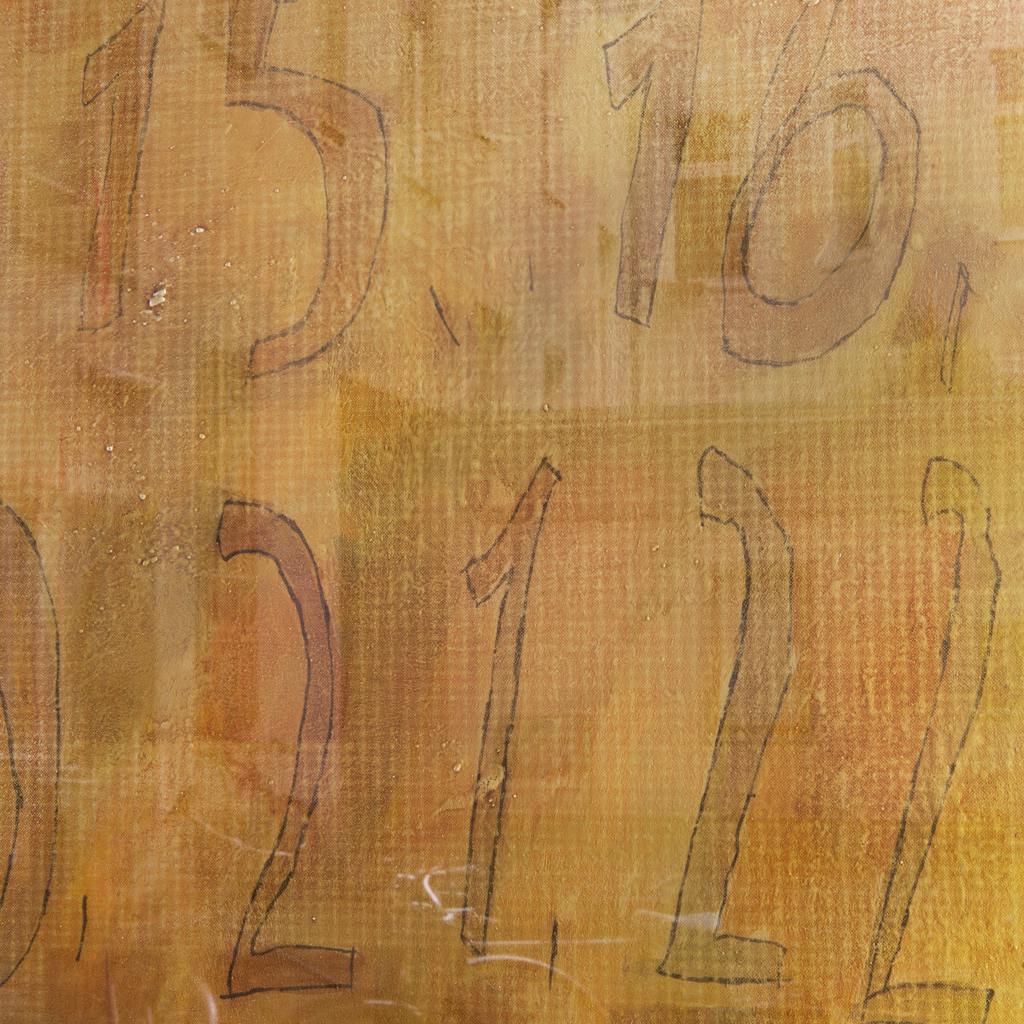

Lukas Quietzsch’s works are productive acts of cyclical self-effacement. A painting is made and then scrubbed out, then made and scrubbed out again until some kind of consensus materializes. The painting doesn’t usually begin with some mindspring from the artist, which is then corrected and honed, but rather a found drawing. Using someone else’s drawing is worlds apart from Warhol blowing up a press photo of Elvis. Pop Art and appropriation repositioned well known things into an environment that alters their reception. Lukas’ treatment of his borrowed motifs — which are decidedly not familiar — is so obfuscated that they become neither his, nor the original artist’s, but instead sidestep authorship and masquerade as some hazy piece of our collective unconscious. His paintings occupy a limbo in which the usual hallmarks of an artistic hand are clouded, as are the recognizable features of appropriation. Pentimenti here is like a screen burn, as if earlier iterations were left so long they indelibly influence the picture, no matter how many changes are stacked on top. A gridded undergirding, made starker by the frottage of washing pigment from the surface, gives the impression of some kind of pixelation. Except this matrix of squares has no influence on the image. Seemingly nothing has an influence on the image — despite every element of the process being devoted to it — leaving the sensation that the paintings could be different if we looked again in five years or five decades.

Sullying the alchemical wonder of painting with the blunt chemistry of photography is just one of many sacrileges towards coherence that Pádraig Timoney commits. His method blocks any easy entry and instead asks his viewers to consider each work as he does: a wholly individual experience, related to one’s other experiences, but not neatly file-able in a chronology or progression. An insistence on extreme subjectivity seems to betray a hope that art can be appreciated regardless of how many differing interpretations are lobbed at it. How we picture life is the lofty question that is suspended in Padraig’s practice, which ventures to bring images of differing physical, temporal and psychological locations into the same space. He treats the viewer as someone who does not need to be led to understanding, but who can rather be dropped into a strange situation and find an inventive way out. His works are marked by admiration at the avenues in which knowledge comes to us — whether through reading the classics or browsing Google Street View. These means of learning are treated as equally as the varied mediums employed in his practice. They can be installed beside each other without hesitation — forcing those who see the combination as sacrilege to reconsider.

It’s important to remember that art has had vastly different aesthetic priorities at different moments in history. The four artists included in this show acknowledge this fact implicitly. What you can see in their work seems to be secondary to all the things that dragged it into existence — the histories, potential futures, collaborations, taboos, slippages, misdirections, shortcomings and hopes. Illuminating any singular position is not their motivation, and often their work instinctively mocks this notion. The audience is instead invited to consider the symptoms of a structure that affects both the artist and the viewer.

Patrick Armstrong