Kaspar Müller

13 July - 7 August 2018

Kaspar Müller at the Downer

13 July – 7 August 2018

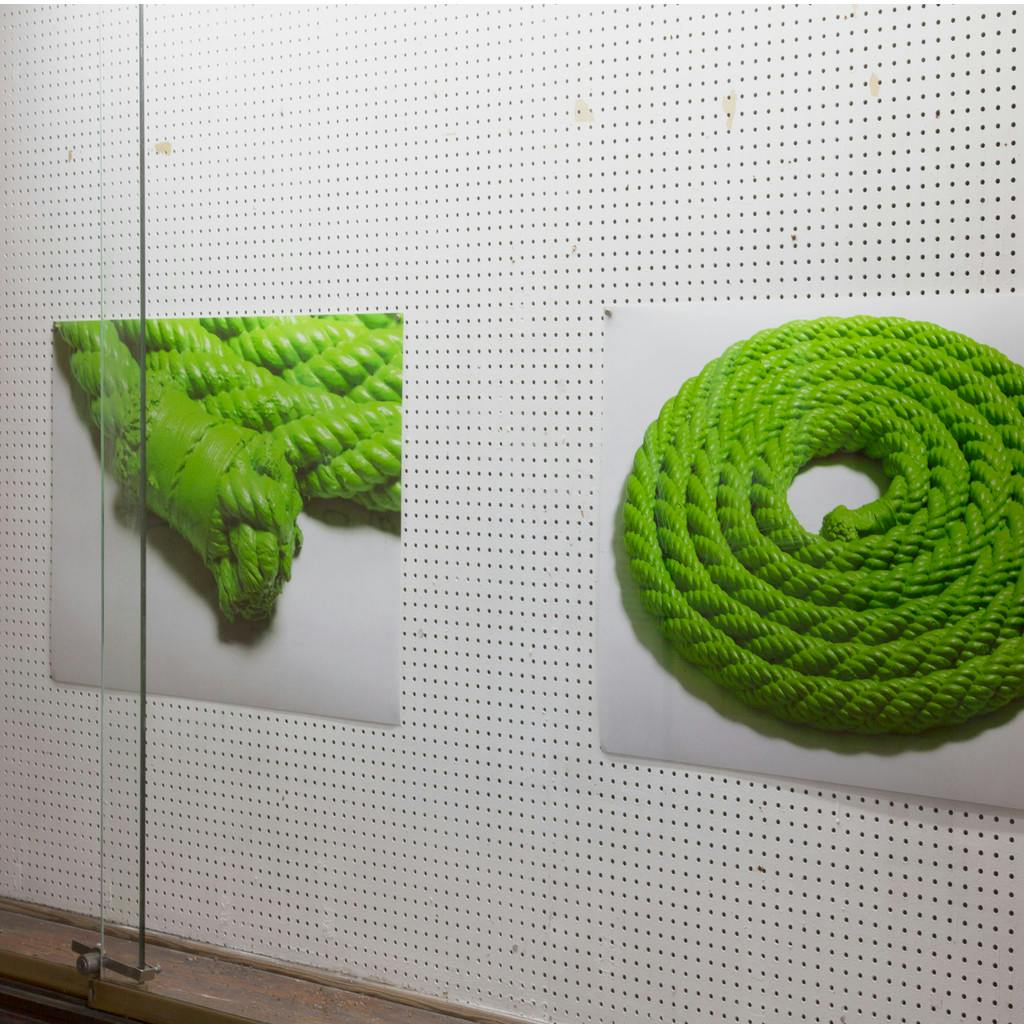

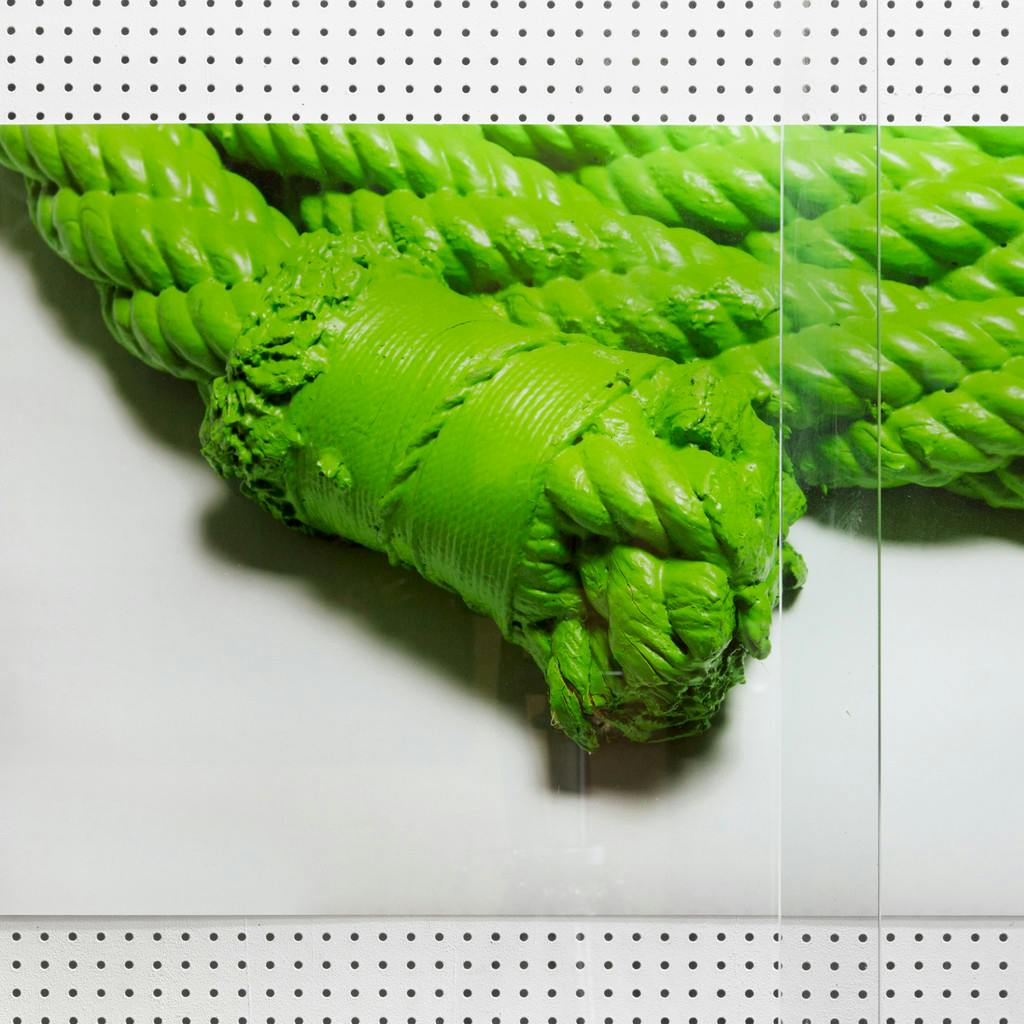

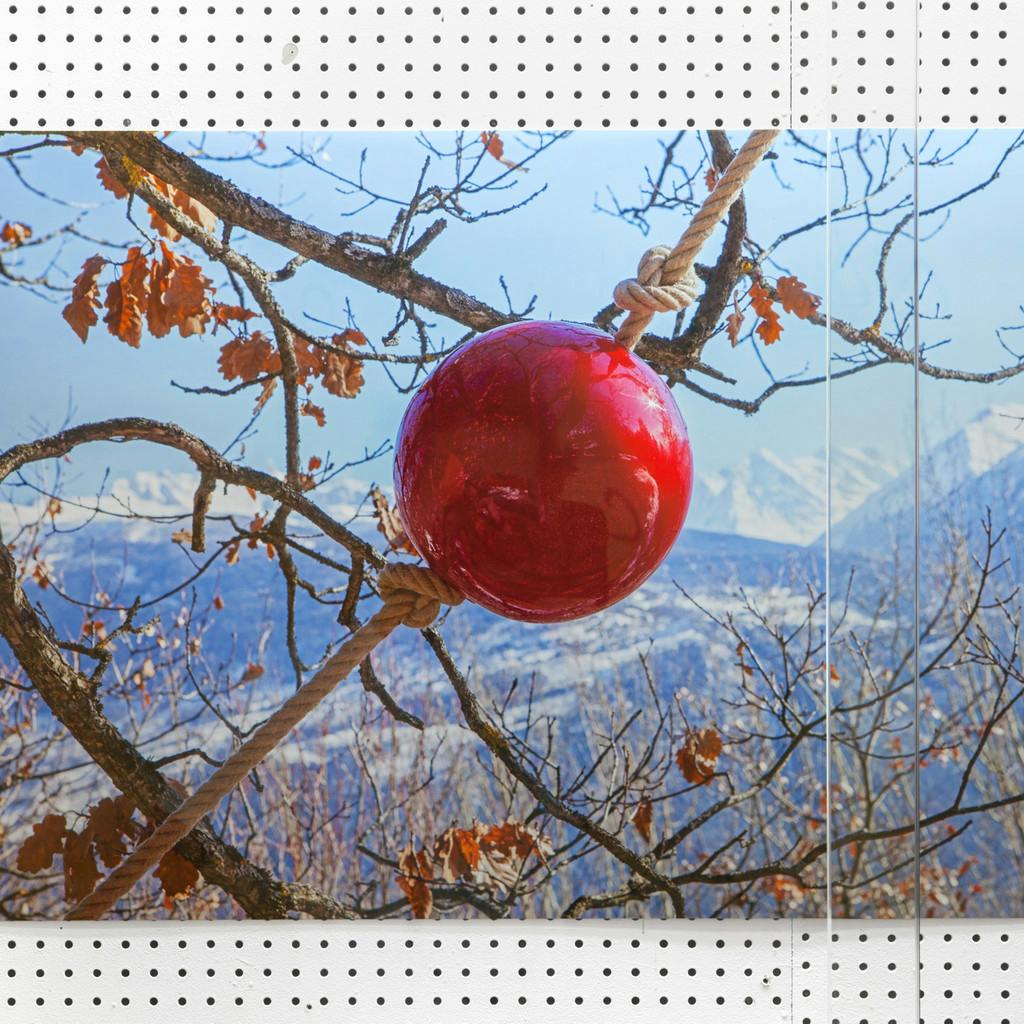

Blown glass balls have a recurring presence in Kaspar Müller’s work, turning up knotted onto long ropes and strung along the ceilings and walls of galleries, art fair booths and once on the outside of a shack-turned-exhibition space in rural Switzerland. They also feature in photographs – sometimes shown alongside their real counterparts and sometimes not. The photos are shot seemingly in situ – at least not against a white backdrop in the manner of art documentation – but rather outside, sitting in the grass and perched in tree branches, or inside, backdropped by dark wood paneling and more glass in the form of elegant room partitions. Staged like bespoke product photography, the images of these glass orbs indicate some kind of life beyond the gallery, but in doing so almost nullify the idea of the originals being artworks. They could just as easily be lawn ornaments.

What does a blown glass bauble represent, after all? As basic as it may be, a beautiful, fragile object with no use value aside from decoration is one definition of an artwork. Conversely, these objects have a strange, poetic power to them. A blown glass ball is a perfectly imperfect thing – it aspires to well-roundedness, but that is ultimately an unattainable goal. Moreover, each was literally created by human breath. And so if these objects can be employed to define art, they ultimately insist on a more nuanced definition. An earlier exhibition of the glass orbs – both real and photographed – took the title “Corrective Detention,” as if the works on view– or perhaps the viewer – could arrive at some new state of being after their internment in the gallery space.

Alternating strategies of elevation and demotion make Kaspar Müller’s practice a difficult one to describe, let alone understand completely. On one hand, he seems perfectly at ease with the power of an exhibition space to inspire reverence in an audience, going so far as to include take out containers, plastic bags and cups filled with hardened acrylic paint in a show that recreated the artist’s studio as a kind of charade. This abuse of power could be irritating if it weren’t for the fact that he subjects his own works – these being the objects he actually makes himself, many of which are the product of intense effort – to a similar kind of degradation. In the same show, the artist included two orange traffic cones – one made of cheap plastic, ostensibly a ready-made, and the other blown glass, which is a mystifyingly interesting thing. The gesture seemed to say, ‘here, both of these are useless now.’ Useless or not, by including both, Müller simultaneously increased the attention I was willing to pay to the totally quotidian ready-made and decreased the fawning I would have otherwise lavished on the blown glass. The sheer act of comparing the two brought them into the same theater and pointed out what an absurd stage they stood upon. It was great.

In an earlier act of self-degradation, Müller pasted dozens of elegant photographs of Lake Zurich – which he shot over the course of a year – onto thin boards that he had painted white and then nailed to the wall. He then painted over the nails in a futile act of attempted concealment. The photos themselves are lush and tasteful. Their presentation was decidedly the opposite.

The exhibition of the Lake Zurich photos resembled a deconstructed book. As I remember it, all of the white painted boards were about the same size and orientation. The photographs were arranged in a similar fashion on the panels, with a few interruptions for those that either warranted their own page or were vertically orientated. It was almost as if someone had torn pages out of an oversized coffee table book – maybe one that someone spilled a drink on, because the panels were warped and wavy from the paint – and hung their favorites on the wall rather than throwing the whole thing away. Eventually, the project did in fact become a book. In it, Müller mixed the photographs of his collages – only noticeable as such through some scrutiny – with the pictures straight from the camera’s SD card. It’s ironic to me that this book ended up winning the “Most Beautiful Swiss Book of the Year” award in 2015.

Irony aside, this series of events is a good illustration of one of the ways in which Müller works, taking up clichés and embodying or reimagining them with equal parts earnestness and knowing satire. In this case, it worked across the aisle – the cliché-lovers loved it, maybe with a small degree of self-awareness, and so did the exacting, novelty-seeking consumers of contemporary art, myself included. The photos of Lake Zurich could just as soon have been postcards rather than artworks – their subject matter refuses to turn itself over to the domain of art (at least contemporary art as we know it). It’s just too picturesque. Wholeheartedly embracing this, Müller sought out postcard images. As he would tell it, the lake is too beautiful to take a bad photo of. And so, through an admitted prosumer’s lens, the images of this lake present themselves to us in a wholly un-motivated fashion. They don’t seem to complicate, question or add anything to their subject. They leave a very narrow sliver for critical reception and do nothing to facilitate it. They don’t beg for more scrutiny because they borrow from a format that doesn’t expect any. They just are. Similarly, their meaning just is. Like an analyst sitting behind you and murmuring, “mhmm” or “go on” as you talk for an hour, if you are meant to arrive at something, you will find your way there. I don’t know how else to put it.

The failure of images (or objects) to live up to their promise of representation is another frequent preoccupation of Müller’s. This failure can come from how we are predisposed to reading them or how they are targeted to prey on our emotions. The canyon between ‘reality’ and the mediated world is something that Müller’s work resides in, or selectively straddles. Beyond the rustic elegance of the photos of his glass orbs, the conflation of usefulness and not that his traffic cones symbolize, and the romanticized, quasi-touristic, yet somehow unreal images of Lake Zurich, the question lurks of how similar manipulation and mythmaking is applied to art.

In a video that stars a talking novelty top hat, this sentiment is laid out pretty prosaically. The hat – which we learn was sewn together by the artist’s mother out of fabrics selected by the artist – was not a first time cast member in Müller’s videos, having climbed its way through the ranks from mere prop to protagonist. This recurrence and gradual elevation could bear some parallel to the idea of an artist ‘finding their voice,’ ‘entering their mature period’ or just becoming more widely known. The hat has paid its dues and now it’s time to hear what it has learned over the course of its years of service and through its observations of the world. Unabashedly, the hat unleashes a diatribe about being elevated from something once useful to something instrumentalized as an artwork. It tellingly finds focus on channels of distribution as a means of hanging on to relevance and caché, ponders the successes and failures of art that tries to avoid this way of being memorialized, and ultimately resigns itself to fatigue.

It is somewhat nihilistic, but at the same time the artworld does have a way of disregarding its own hypocritical trappings in favor of whatever keeps the machine running smoothly. Müller’s work – to continue the metaphor – is like a wrench in the gears. When probed on the subject in an old interview, Müller quips that true cynicism would be letting all of these abuses of a system, medium or means of communication go unchecked. “There is nothing more cynical than to see people in front of magic tricks and falling for it,” he said. It seems to me that his motivation is not to stop the show all together, but rather to clue the audience in on their way out. It’s fun to enjoy the trick and even more satisfying to know how it’s done.

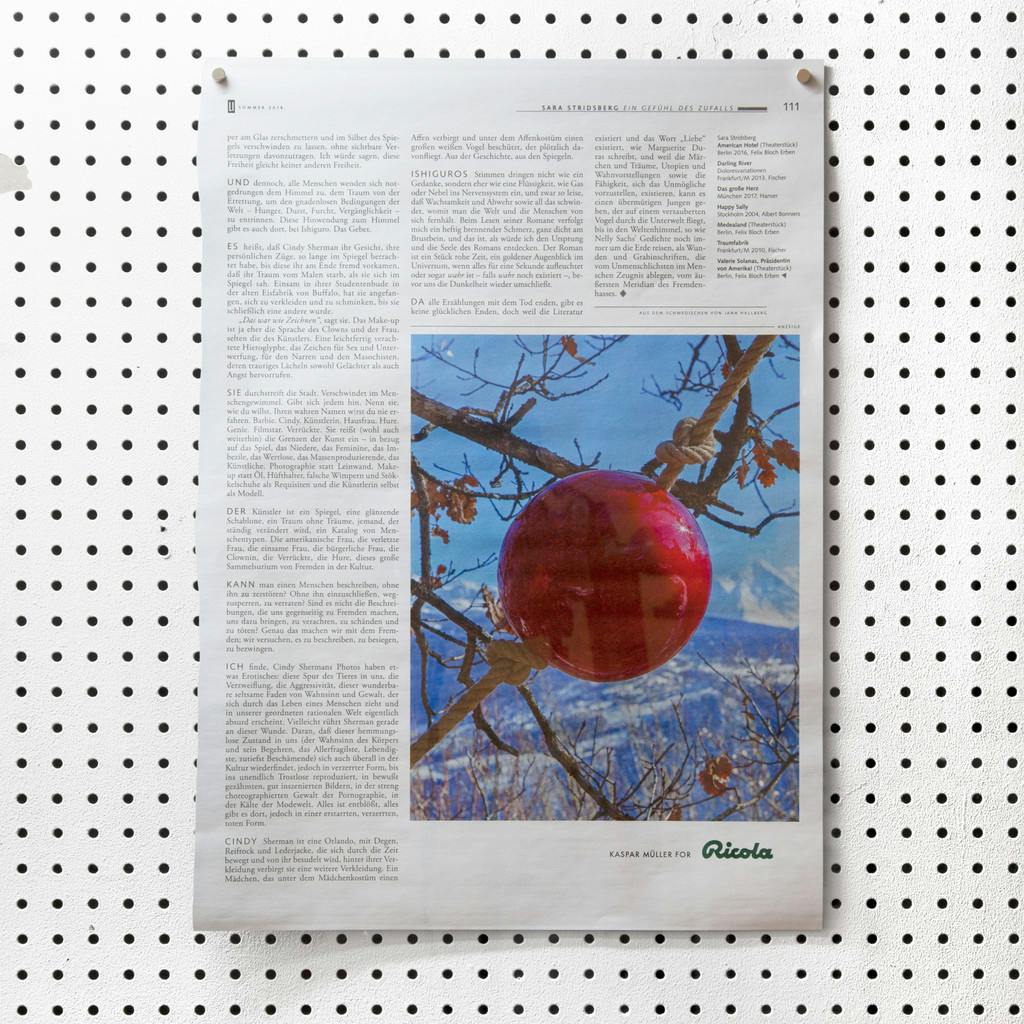

In order to do this, Müller undermines the conventions of the reception of art as it has come to be today: a hydra of communication, promotion, advertising and social posturing. He still exists within this system – it’s more or less inescapable – but many of his actions as an artist try to peel the curtains back a bit. This can happen when he gives certain artworks unceremonious treatment: often using cheap commercial printers to print beautiful images badly, or pasting beautifully printed images onto hastily painted pieces of cardboard. Or when he repurposes earlier works in new exhibitions, thereby resurrecting them from the static land of the archive and animating them anew. Or when he includes objects that have served a long and useful life outside of the realm of art: antique armoires, materials from construction sites, one could argue that even the take out food containers could fit into this category. Or when he brings promotional materials back into the context of the gallery: an advertisement he shot for Ricola, for example. Or, finally, when his works directly bootleg other artists: he has taken up Julian Opie, Heimo Zobernig and others. Sure, all of these maneuvers can be looked at as cynical, but better that than complacent.

It’s funny. Despite all of this, I still don’t feel like I understand Kaspar’s work completely. It can be austere or contrarian. It can often be frustrating. It also does slyly tackle the shortcomings and hypocrisies of art. But all of this aside, the things he makes contain something unsayable, strange and moving. They celebrate life in its uncertainties and contradictions, and ask their audience to consider them. So for all the criticality and self-awareness that I have read into his work, I think that there is a parallel set of beliefs that can’t be overshadowed: a real, earnest belief in art, and a fascination with its affective capability. The fact that art can resiliently stand up to so much interrogation is as much a part of Kaspar’s work as his line of questioning.

Patrick Armstrong