Anne Libby

16 September - 27 October 2018

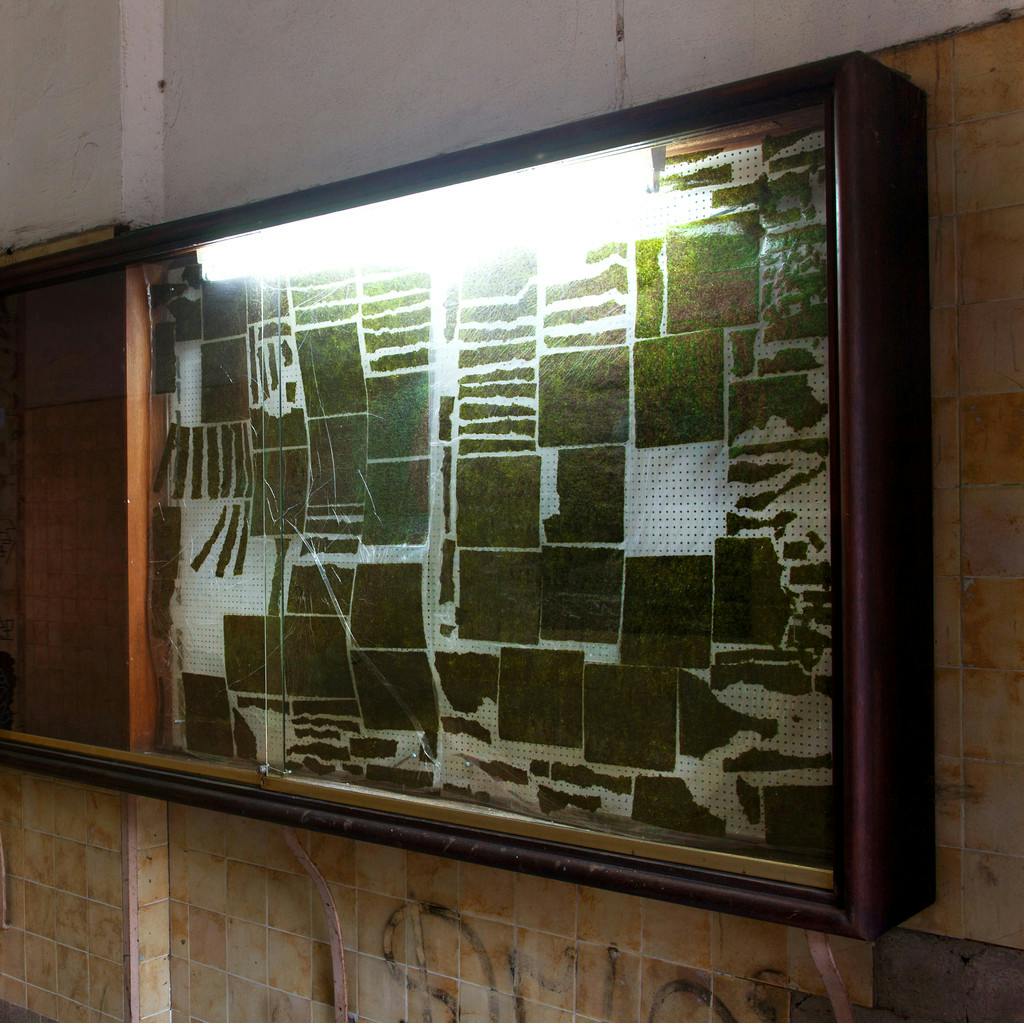

Anne Libby at the Downer

16 September – 27 October 2018

At some point in 1990s a subset of the culinary world realigned itself behind an idea called ‘nose to tail eating.’ This meant that when an animal was slaughtered for consumption, great care would be taken not to waste any part. Bone marrow made a comeback, as did cuts of meat that were generally looked at as substandard or otherwise unappetizing. Snouts, hooves, ears, livers and hearts all found their way onto menus. Naturally, this movement – not that it was a new idea by any means – dovetailed with the less stringent, but nonetheless related push to source produce and livestock from within a certain distance to the restaurants that served it. A new emphasis was placed on using what was available to you and knowing these materials intimately.

It’s not a perfect metaphor, but somehow this only tangentially related movement comes to mind when I think about Anne Libby’s approach to making art. At the heart of her sculptures are materials that are intimately known to most of us and generally agreed upon as undesirable: plastic furniture, venetian blinds, and plywood – the stuff that makes up the cheap, flexible and otherwise impermanent world within which we all now reside. Libby takes these things up and gives them hopeful new lives. In so much of her work over the past years, Anne seems to work ‘nose to tail’ – perhaps with extra emphasis placed on the offcuts.

She has made sculptures out of eviscerated folding tables, carefully and artfully cutting away the usable tabletop. They are shorn down to their hinged, tubular steel skeletons, revealing the sinuous hollow-core structure just beneath the skin. Dictated more or less by the structures underneath them, the cut sections are symmetrical and, with their gently curving lines, vaguely organic. Butchered as they may be, their treatment belies a kind of reverence. Libby uncovers the engineering ingenuity that gave the original furniture its utility as a product, rather than simply a table – which essentially is just a flat, raised surface. The resulting sculptures are wholly new forms as well as celebrations of an existing one. Just as an animal doesn’t exist without joints, tendons, bones and all the rest, observably, neither does a polyethylene folding table.

The mass produced originals are far less recognizable in Libby’s sculptures that include venetian blinds, as they have been deconstructed wholesale and repurposed. Single aluminum blinds, which I imagine must have been unthreaded by the artist herself, are fastened around the outside of small wooden cylinders by wire nails. They trace the edges of larger pieces of CNC-routed plywood, and are intermittently slotted in, unaltered, between changes in the work’s topography. Together with the wood they encircle, the undulating forms are arranged together in accumulations that remind me of the exploded- view diagrams of industrial and product design.

The metal blinds, with their standardized length, half-dictate how the larger sculpture should be created around them while at the same time remaining oblivious to their inadequacy for the given context. Each slat is punctuated by holes on both ends that were previously used to string them together and the slats are often not long enough to wind a continuous line along the routes they embark on, so these are interrupted by the occasional seam. In using them, Libby has adopted a material standard that bristles against common thinking about artistic expression – that an artist’s choice of materials is a realization of the best (or most expedient) way to illustrate their ‘vision.’ She has instead purposefully restricted part of her practice in order to include them. To continue the culinary metaphor, it’s as if a box of turnips and nothing more arrived from the community farm share and one decides to cook a multicourse meal using only them and the spices on hand in the kitchen.

Of course, subscribing to a farm share and dutifully cooking (and consuming) its contents is an ideological choice. Using cheap, commercially manufactured goods as the raw materials to make art is basically antithetical to the ideals behind a farm share, but to me it represents an artistic ideology that strives to connect itself to the world we live in by using what is given to us. Both demonstrate resourcefulness through restriction. Rather than beginning with a blank slate, there is some prerequisite that demands inclusion in the finished project, undeniably altering the course of its conception and realization. This isn’t so different from contemporary life where we have to negotiate all manner of prerequisites – from debt, to family commitments, to whatever. Our existences are in some part dictated by our obligations.

Anne Libby’s sculptures are decidedly not ready-mades and decidedly not sculptures that happen to include tables, bits of other furniture or window blinds in some kind of larger scenography. Instead, they incorporate these prerequisites as a given – as a foundational material that can be tested, reconfigured, experimented on, and made to express something beyond itself. As far as I can see, she treats things these no differently than more common art-making materials; they just require a different kind of manipulation. But their histories and social signification are so far outside of the realm of art that the larger objects they are integrated into become charged with surrealism. It’s like seeing two realities simultaneously – one being the aluminum window blind as we commonly know it and the other being that same object in its new use, which seems almost profane, if only because we are so used to seeing it in its normal, prescribed daily life. This feeling of double vision is also partly because Libby’s work displays none of the slick, fabricated polish of something from a factory conveyor belt. Instead, her sculptures are assertively handmade, guided by association and spontaneity, unabashedly irregular, despite some of their component parts.

They also play to their own strengths a bit, and in the end it’s a winsome sacrifice that Libby makes. While they don’t look like they came off an assembly line, they nonetheless refer to them. Many of her towering assemblages are dotted with uniform, oval knobs at regular intervals, as if they are keeping rhythmic time or marking the stories of a building. Anne lives in New York, and I can’t help but see glimpses of the crumpled channels of Frank Gehry’s 8 Spruce Street or the faceted jumble that somehow coalesces into Herzog and de Meuron’s 56 Leonard in the things she makes. But her work is only really architectural in the sense that it doesn’t obscure the structure necessary to make something stand upright. The repetition and rhythm contained within them can remind one of the monotony of repetitious labor, the uniformity and regulation of a residential subdivision, or the intervaled bumps of solder on a computer chip. Oscillations in scale between the micro and macro give them the quality of an optical illusion that seems to change entirely depending on how one focuses their eyes. They would still be beautiful if they weren’t partially made up of these scraps of feverish capitalism, but the fact that they are gives them an alluring and confounding complexity.

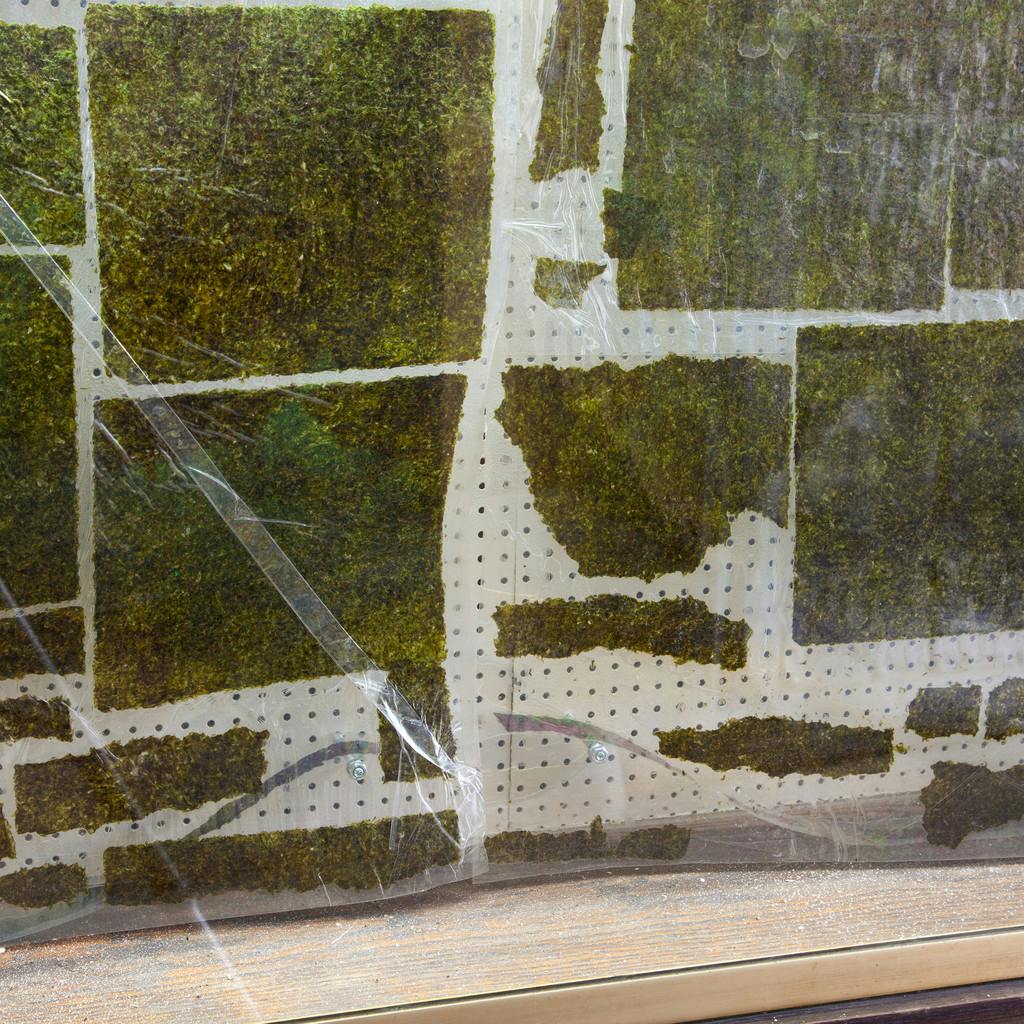

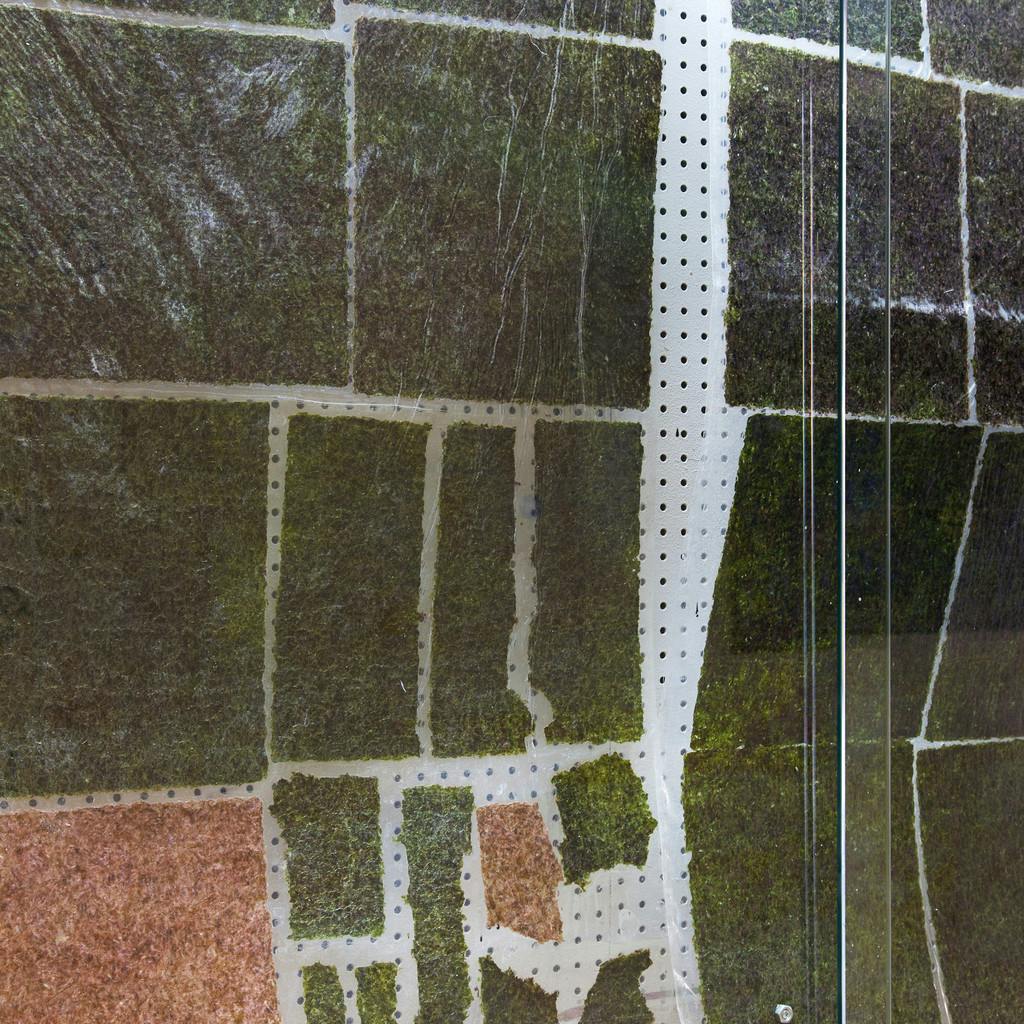

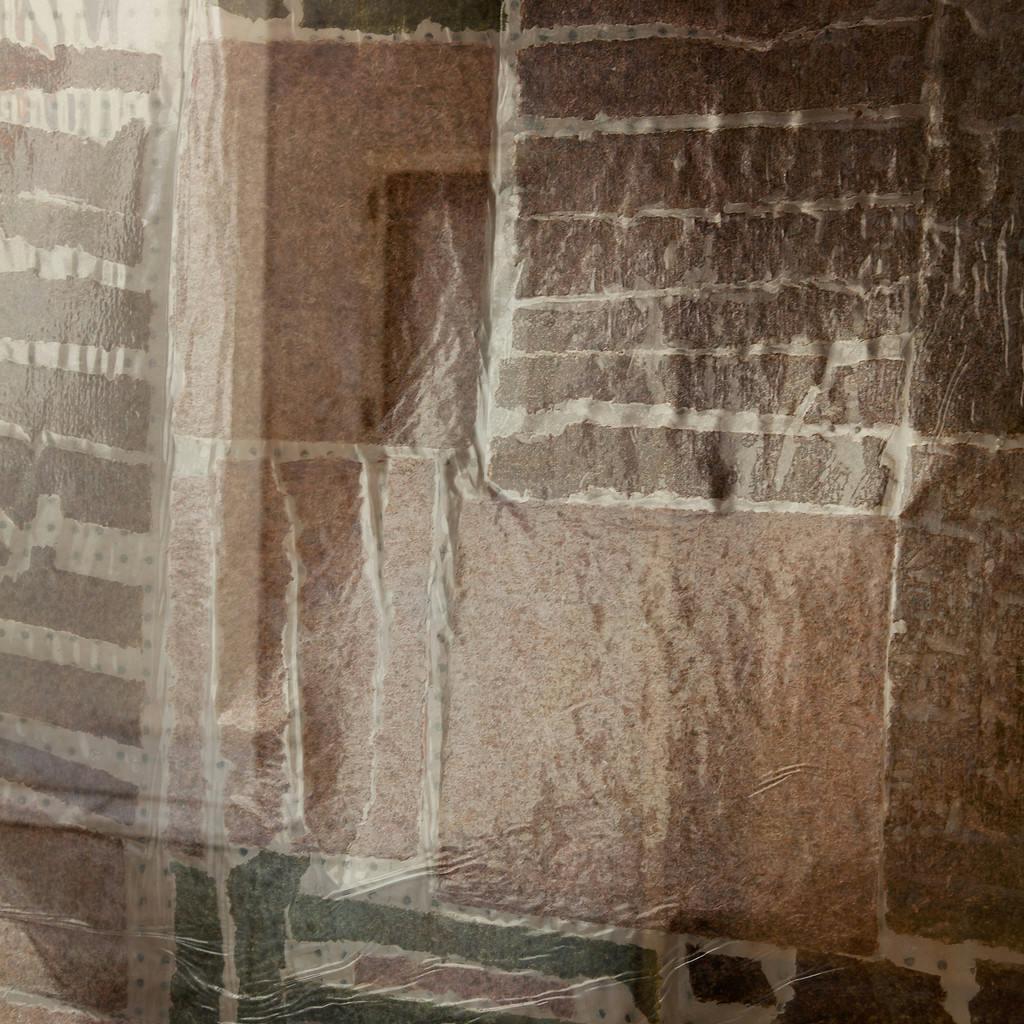

Of course, I need to return to food, and this time it’s not necessary to write metaphorically. Libby has begun to include organic – edible – material in her work. Garlic husks and sheets of nori preserved in resin or laminated into long mosaic panels, both of which find their way into larger sculptural assemblages. At first I assumed these new material interlopers were a kind of concession to humanity – a visualization of the fact that while, yes, we’ve built ourselves into a claustrophobic hellscape of industry that we may never escape from, we still need to eat! And I still think this is somewhat true. But the nori nagged at me. Libby composes accumulations of torn fragments in varying widths and lengths, and then runs them through a laminating machine. The result is beautiful and translucent – reminiscent of unspooled film or solar panels – but this act of framing also made me realize that nothing grows into sheets of nori. Indeed, they are products too – the result of shredding, drying, flattening and reconstituting something that was previously much more recognizable as a plant. I don’t think it would be a stretch to argue that this process bears resemblance to making plywood or particleboard.

But is this disheartening? I don’t think so. Art, for all of its utopic promises of escape, should – at its best – also be a mirror held up to society. It’s impossible to argue that we don’t live amongst particleboard furniture, pre-fabricated window treatments, processed food – however high in iodine it may be, and disposable everything. To exclude these things from the artistic palette would be to ignore reality. To include them is an act of agency through reclamation, as well as a nod to our shared experience. In a world that is increasingly packed with prerequisite obligations, it’s a small comfort when art can at least empathize.

Patrick Armstrong